Teaching Indigenous Heritage in a 6th Grade Classroom

By Jonathan Peraza Campos

Narrative Writing Unit

In my 6th grade class in the Atlanta, Georgia metro area, I emphasized Native American and Indigenous stories during my language arts unit about narrative writing and story elements in the fall of 2024. To enhance learning, we used tools like Portraits of Tenochtitlan and the Living Maya Time website.

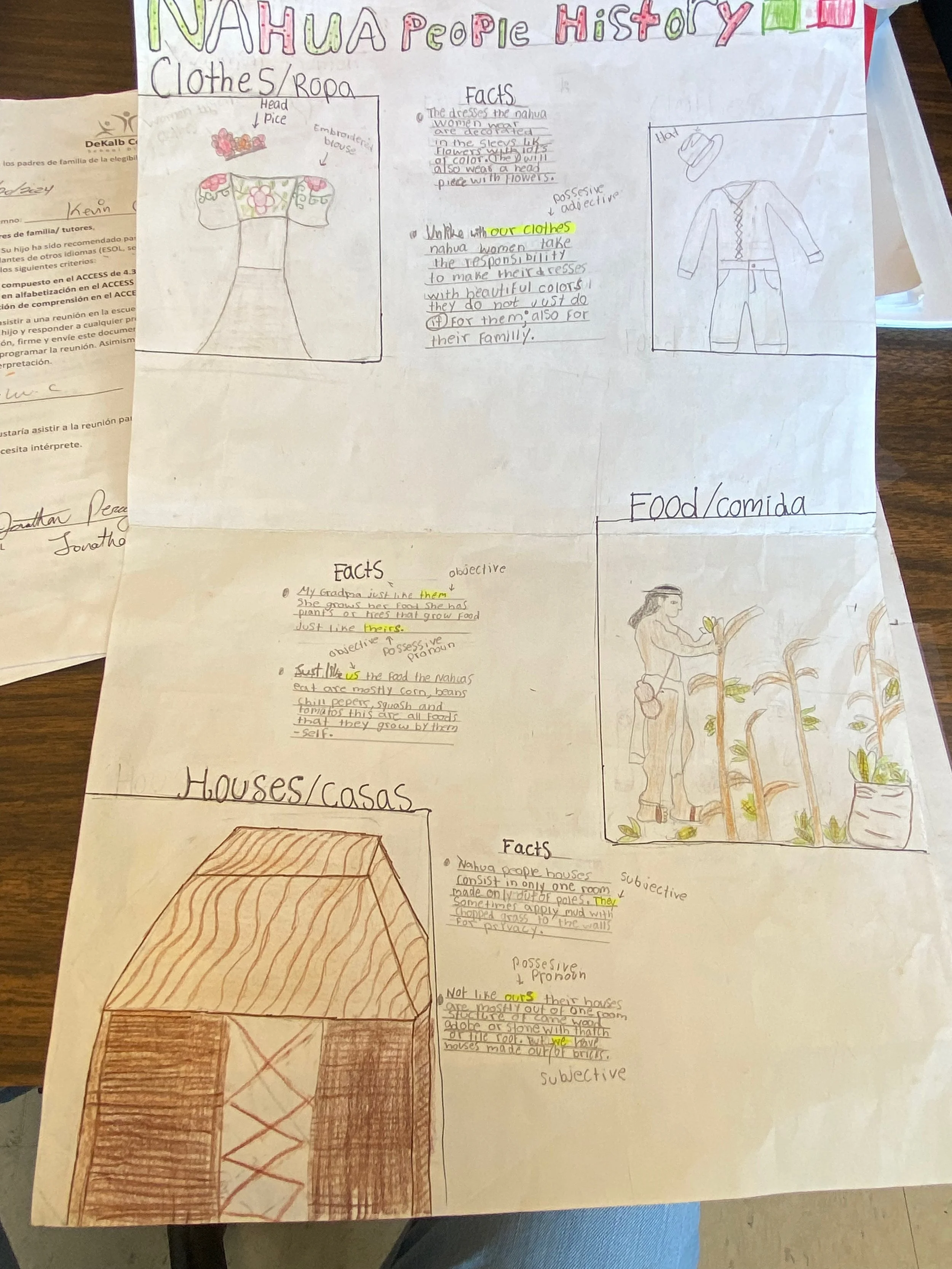

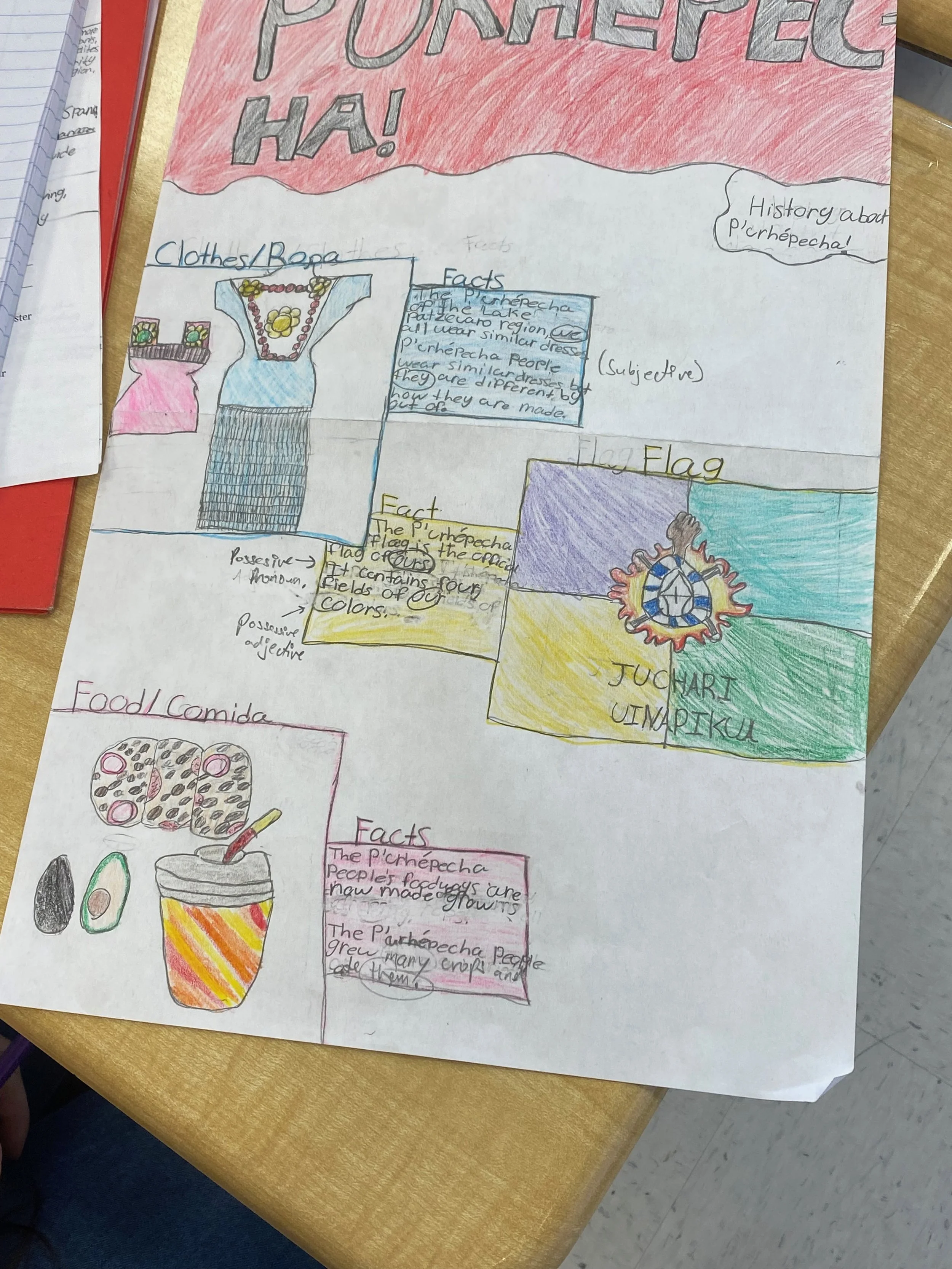

Most of my students are of Latin American descent with roots in Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Colombia. Other students are of African, African American, Vietnamese, and Bengali heritage. To research the Indigenous peoples of Georgia and to dig into their Indigenous roots, students created posters that represented ancestral histories and modern Indigenous culture while also using different types of pronouns (subjective, objective, and possessive) to articulate their research findings. We started by using the Native-Land.ca website to locate data on Indigenous lands.

Students engaged in family history research, asking family members about their countries and regions of origin. My student Victor told me, “I learned that my parents are Lenca just like Berta Cáceres.” I responded, “You know that means that you’re Lenca too, right?” He now doodles the words Lenca and draws the Lenca flag anytime he can. Another student found out her grandmother and father are P’urépechá people, inspiring her to learn more about her Indigenous ancestry and family.

Teach Central America Week

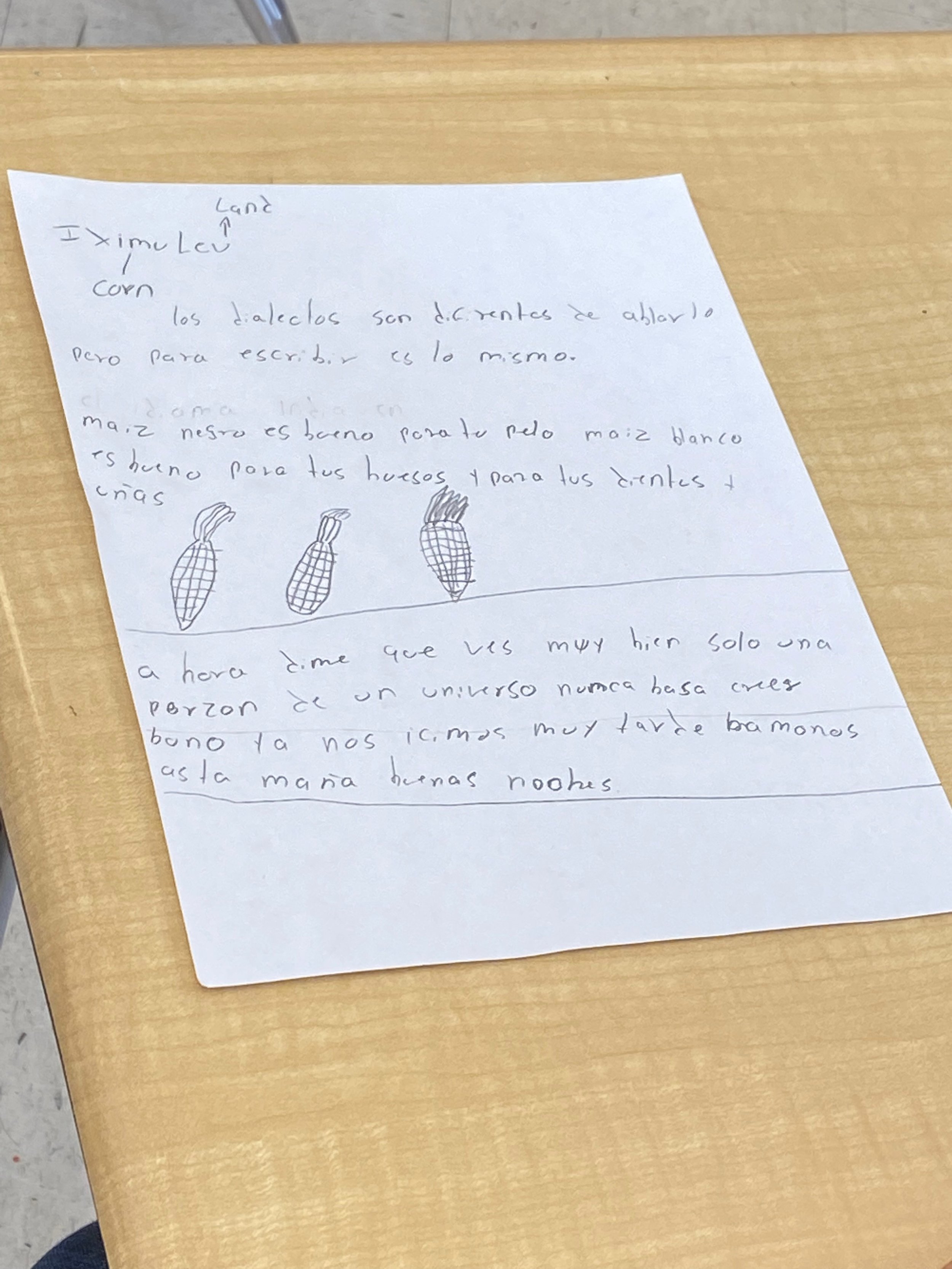

By the time we got to Teach Central America Week in October, we studied the Maya K’iché creation story from the Popol Vuh to learn about the K’iché’s belief about how humans originated and the sacred purpose of corn in our thousands-year old existence. For many of my students who come from Maya-Mam heritage and speak the Maya-Mam language, this was the first time they had learned about their culture and history in school, despite their large presence in the metro-Atlanta area. One student, Frederic, said, “After learning about the Popol Vuh I decided to do more research and learn about my Mayan culture. I learned that we are thousands of years old.”

In alignment with Teach Central America Week, I also shared my culture and background with students as a Salvadoran and Guatemalan. I discussed the brutal history of U.S. imperialism and fascism in El Salvador, focusing on the very real stories that my mother told me about her experiences during these U.S.-funded armed conflicts.

To emphasize our resistance, I used a biographical profile about Farabundo Martí from the Teaching Central America website. I also dressed up as Martí in celebration of our school’s Latine Heritage Spirit Week. I shared with the students that my mother’s trauma surrounding what she lived through during her childhood stopped her from helping my family connect with our land and heritage. Today, I am compelled to teach the truth and use culture as a tool for empowerment in the classroom for my students.

It’s been beautiful to see how these lessons have informed my students’ identities, confidence, and storytelling. Some of my Mayan, Chatino, Lenca, and P’urépechá students are becoming comfortable and empowered to identify themselves as Indigenous.

Poetry Unit

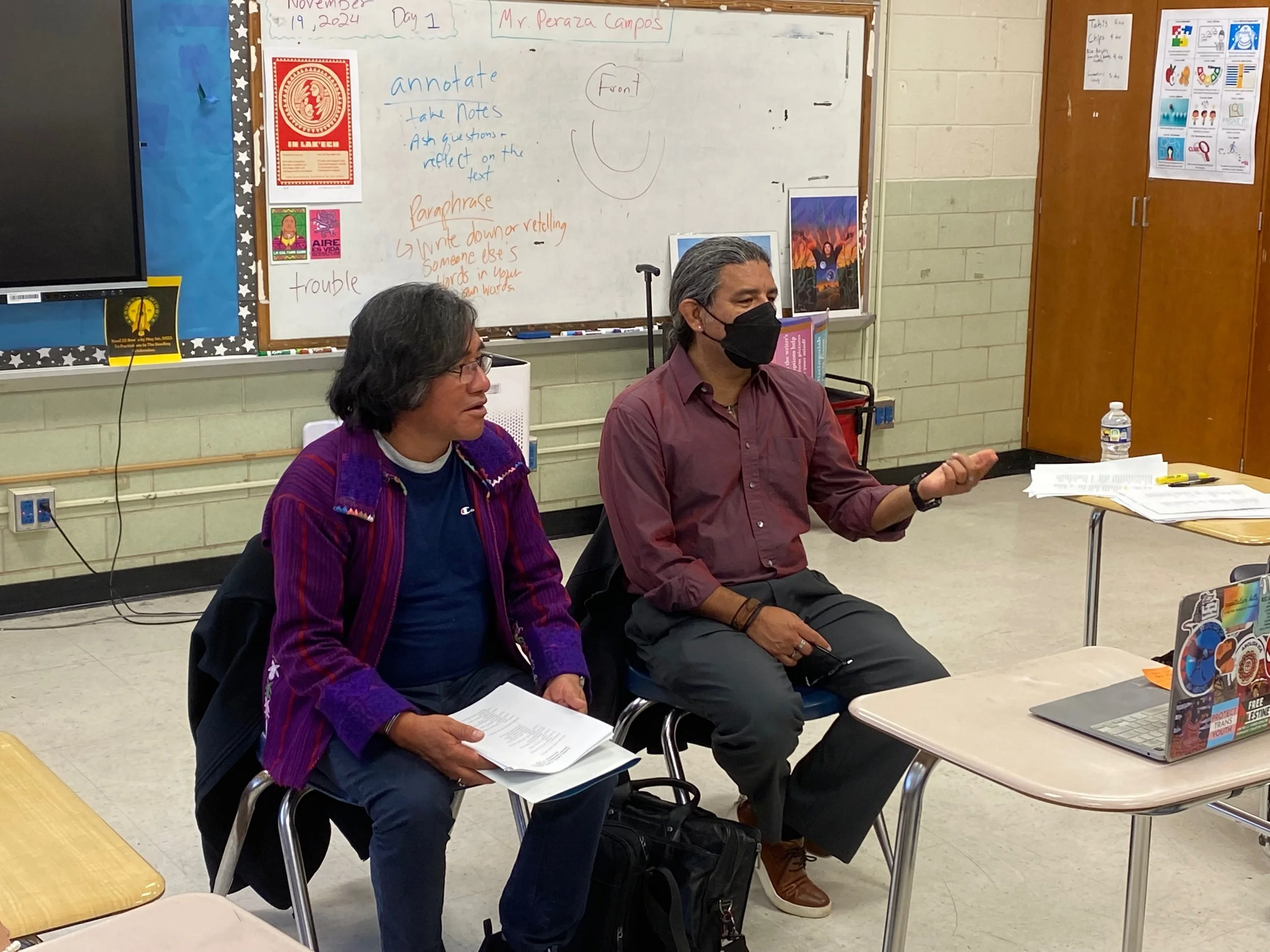

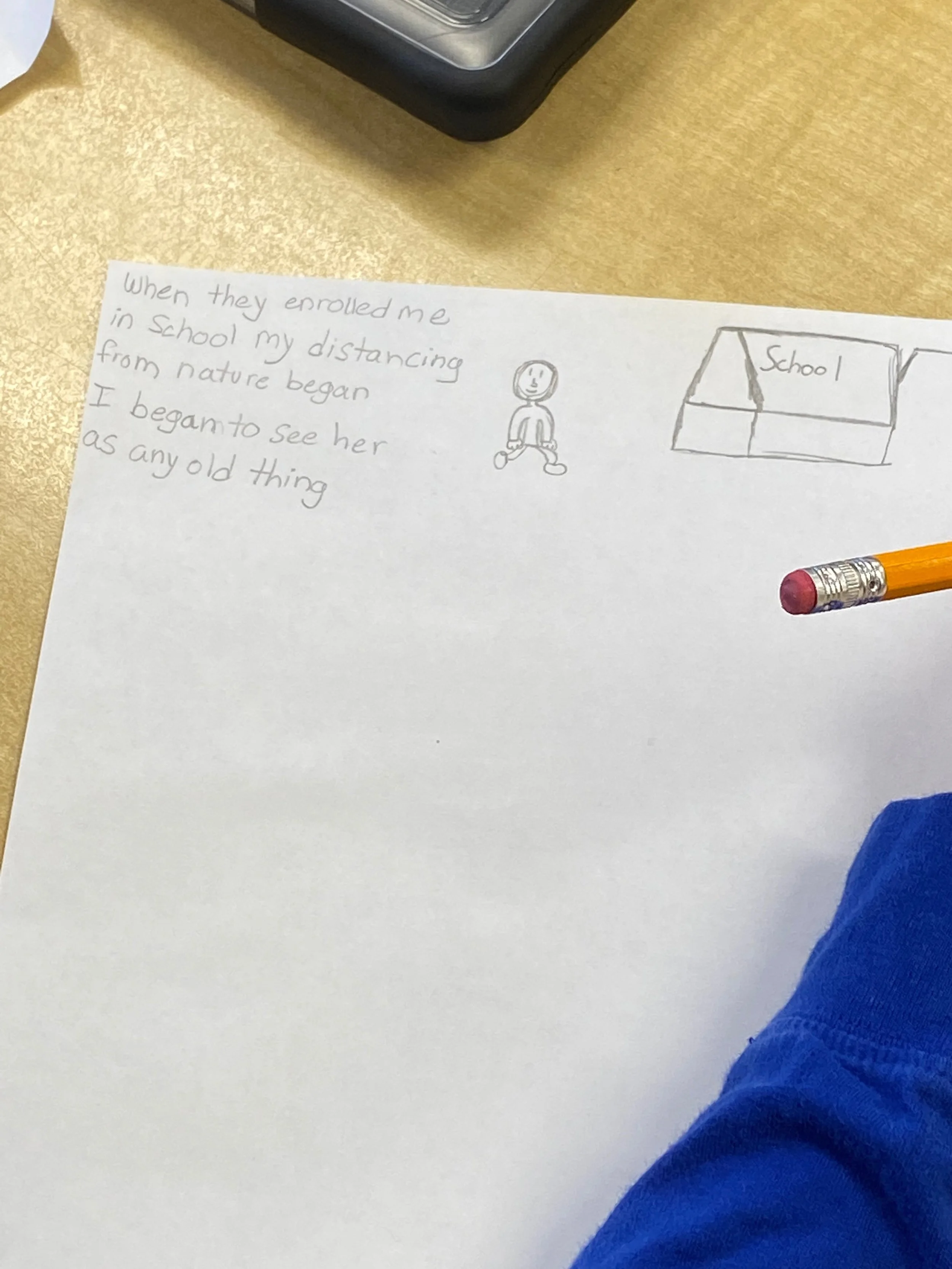

During our poetry unit in November, my class and my school community were blessed with the gift of Indigenous Maya scholars, poets, and spiritual leaders sharing their knowledge and stories with us. Maya-K’iché professor Dr. Emil Keme from Emory University, a Teaching Central America advisor, invited Daniel Caño, a celebrated Maya-Q’anjobal writer, to share his art and teachings with our class.

My students — and many other children in our school community who watched virtually — learned about the thousands-year old history of the Maya people, including the recent history of colonialism and genocide that drove many Maya migrants to the United States. Keme and professor Caño’s teachings showed my students the power of listening and connecting with Mother Earth and the living world around us.

They empowered my Maya, Lenca, Chatino, and P’urépechá students to remember and (re)connect with their ancestors and heritage. One student who recently migrated from Iximulew (Guatemala) was so happy to finally be able to speak his native Q’anjobal after being made fun of for his developing Spanish. He accompanied Sr. Caño in reading the original poetry written in Q’anjobal. My students also read Sr. Caño’s poetry in English alongside his readings in Q’anjobal and Spanish.

Words aren’t enough to describe the decolonizing magic of this visit that has healed and nurtured me to continue my work as a decolonial ethnic studies and Central American studies teacher.

Jonathan Peraza Campos is Teaching for Change’s Teach Central America Program Specialist and also a 6th grade teacher in metro-Atlanta, Georgia, where he teaches about Central America all year long.