Teaching Central America: Celebration of Learning

Bruce Monroe @ park View Elementary School

In a country that is deeply divided, the staff at Bruce Monroe @ Park View Elementary School show how to bridge that gap with a schoolwide exploration of students’ history and culture — and a commitment to activism for justice.

This was evident in the 5th annual Teaching Central America Celebration, a showcase of their multi-week study of Central America. With more than 50% of their student body having ties to Central America, the unit of study reflected the school’s mission to provide culturally responsive teaching and equity-driven instruction. Coinciding with the school’s first quarter theme of identity, the study of Central America drew on resources from the school’s collaboration with Teaching for Change’s Teach Central America Week and the Pulitzer Center 1619 Project Educator Network. (The school took a similar in-depth approach to a study of the Black Lives Matter principles.)

Students recite daily “In La'kech,” the Mayan inspired poem, “You are my other me. What I do unto you, I do unto myself.” As the school overview of the unit notes,

This is a poem our students recite daily to remind us of the importance of each of us in our community. The focus of today’s celebration is insight into our individual identities, as well as our identity as a school.

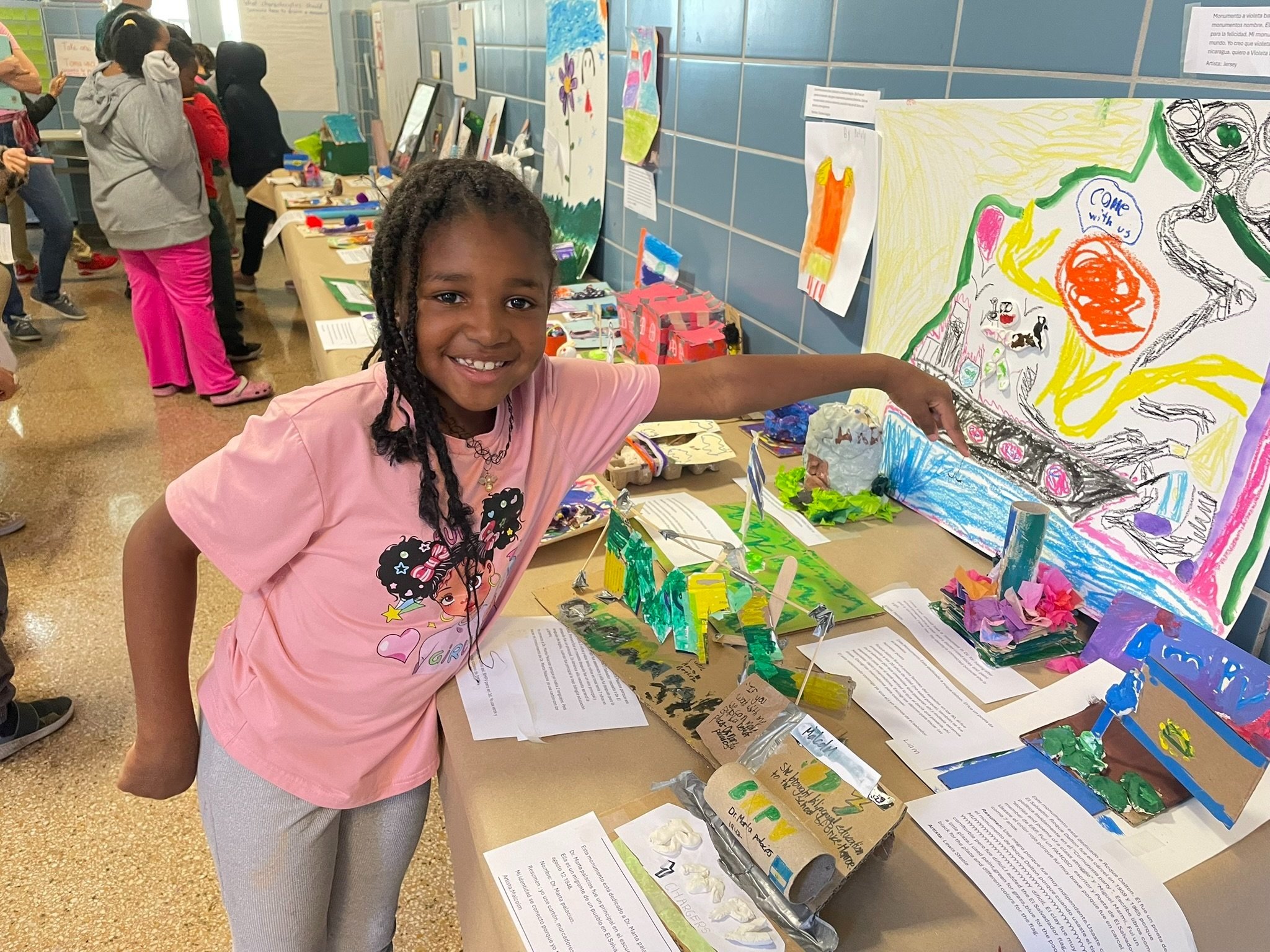

On the day of the celebration, October 24, 2024, student learning was displayed for their peers, family, and community. Visitors received maps and handouts that outlined the school’s units of student from early childhood through 5th grade.

Hallways, turned into exhibitions of student learning, were festooned with anchor charts, student art work, zines, performances, digital resources and activities that allowed visitors to learn about and interact with the knowledge teachers and students had constructed. Students excitedly roped in visitors to huddle around their art work and writing and to share their learning process.

Teaching for Change staff and volunteers attended the day-long celebration of learning. Here are some of the observations by Marcy Campos and Andrea Vincent, accompanied by excerpts from the official event program for each grade.

In the 1st-floor hallway, a classroom of 3rd graders, clip boards in hand, sprawled out to read and interact with large sheets of chart paper documenting in words and photos the oral histories kindergartners and their teachers conducted with Central American parents and older students who had immigrated from Central America.

Focusing on similarities and differences between education in Central American and the United States, kindergartners asked questions about school uniforms, recess, the cafeteria, travel to school, and whether or not English was taught.

The 3rd graders completed a reflection on what they learned from the kindergartners’ exposition in drawings and words: What did they see and think about what they saw? How could they connect this learning to their lives and other bigger issues or ideas.

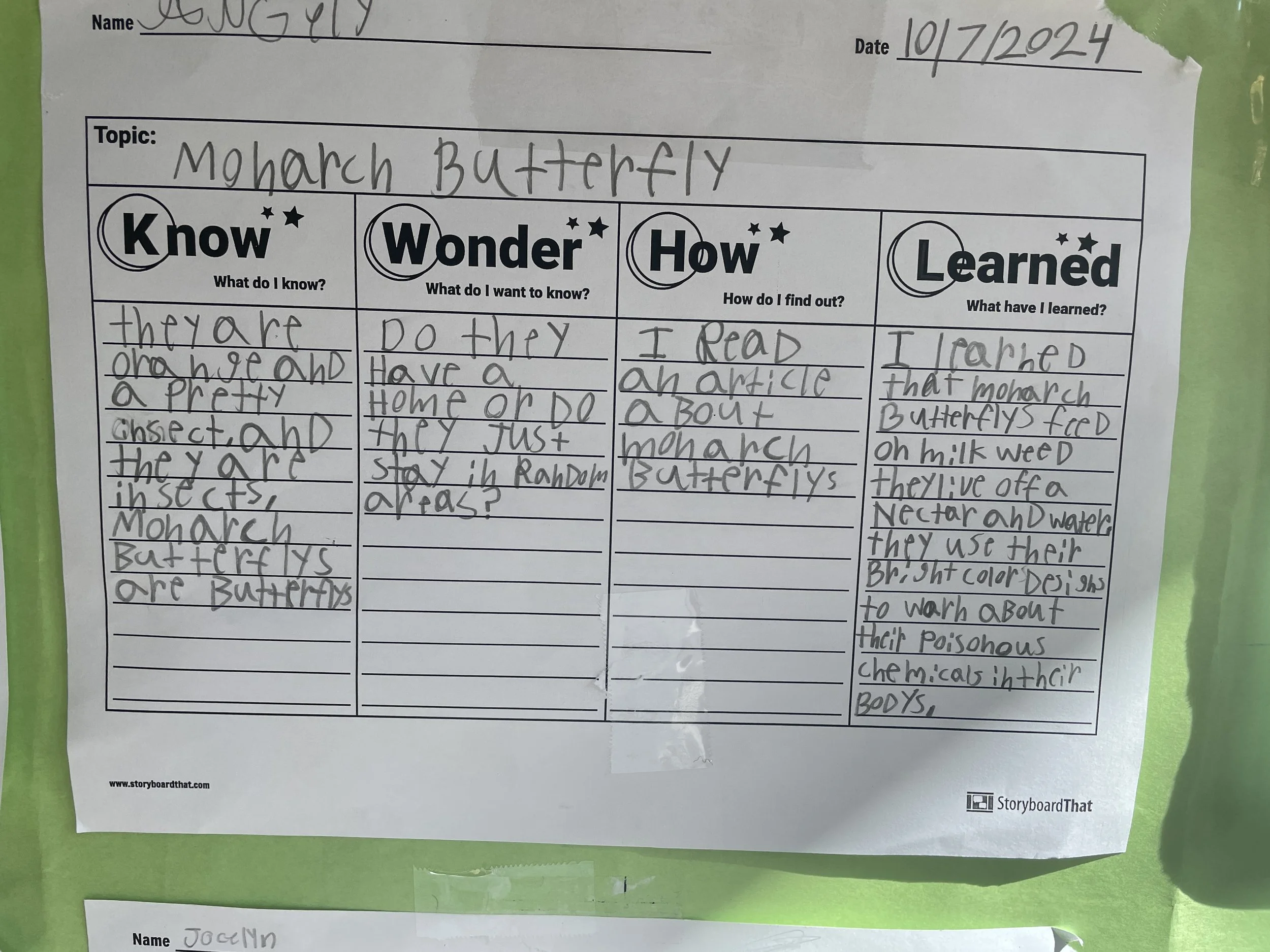

A kindergarten KWL chart listed what students knew prior to the lesson, what they wanted to know, and what they learned.

In the 4th-grade hallway, students created an interactive forest that taught the audience about different organisms in the Central American ecosystem. It sought to connect questions of adaptation in the natural world to Indigenous cultures and the individual identity.

Younger students sat around a paper mâché construction of the ceiba tree, as 4th graders explained its sacred role in Mayan culture. After learning that the roots represented the underworld and the home of Mayan ancestors, the trunk the human world, and the branches the home of the Gods, they were ushered to an art table where their hands were traced on green construction paper and glued to the trunk of the tree.

Every grade participated in the study of Central America, as outlined below.

Pre-K

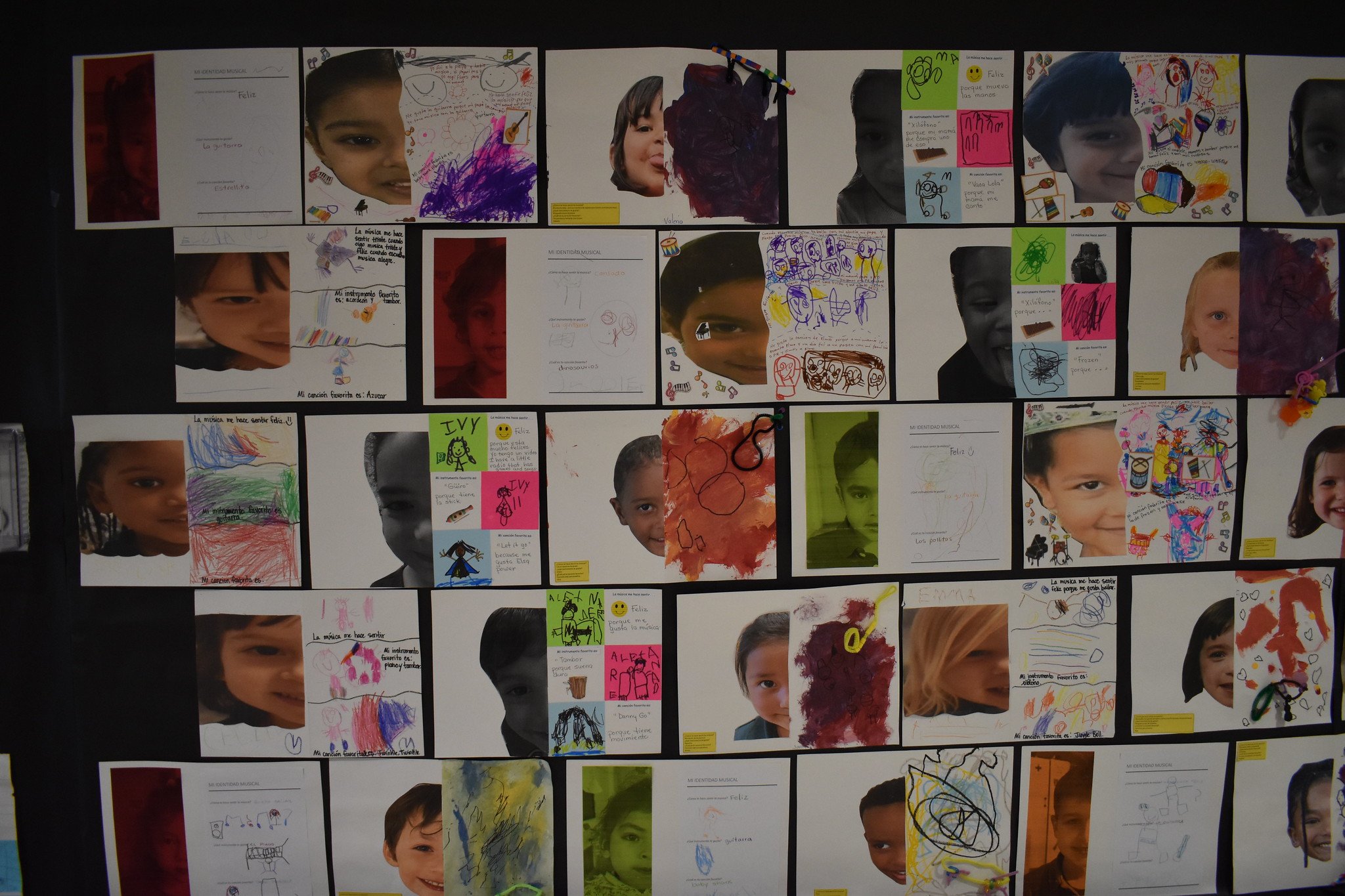

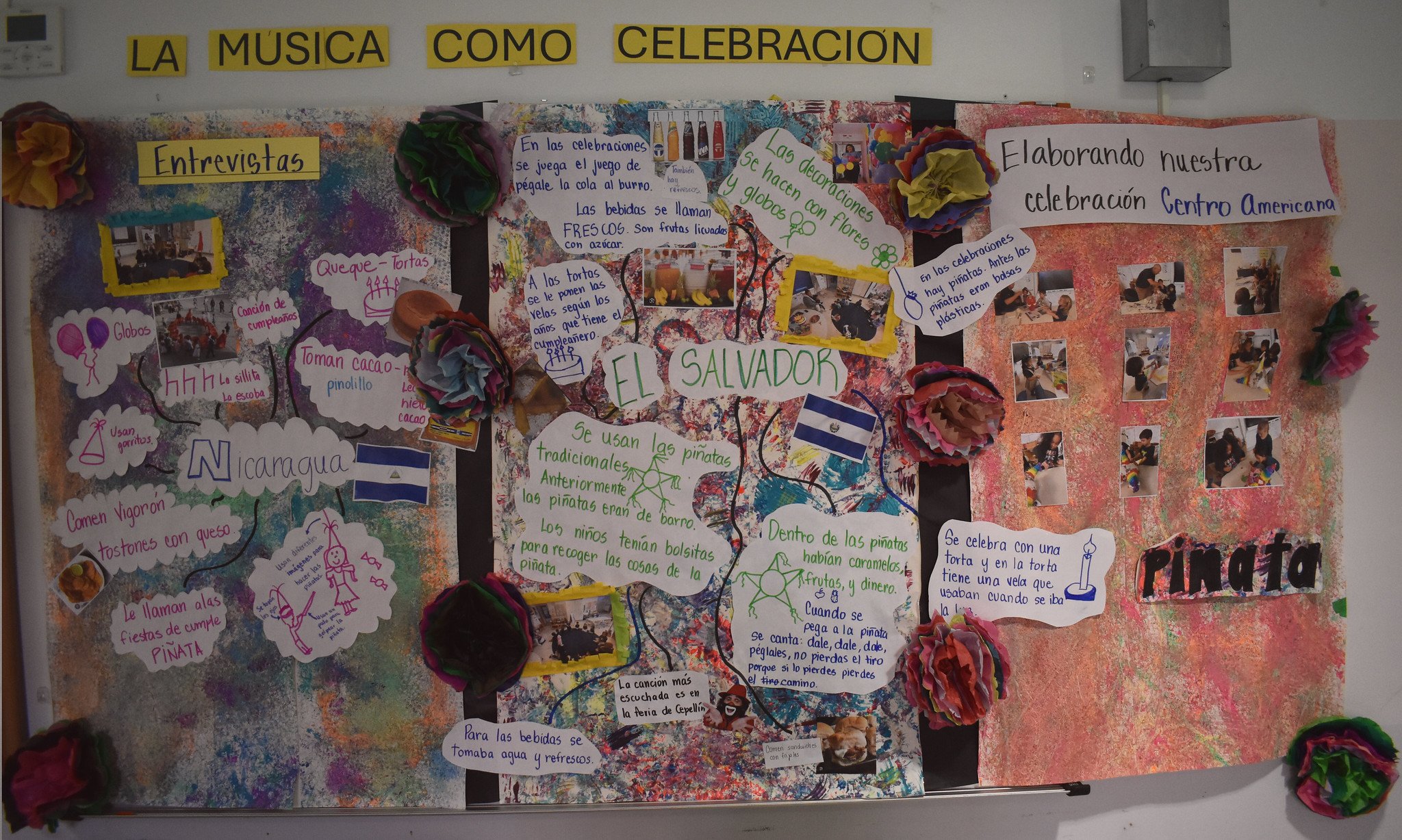

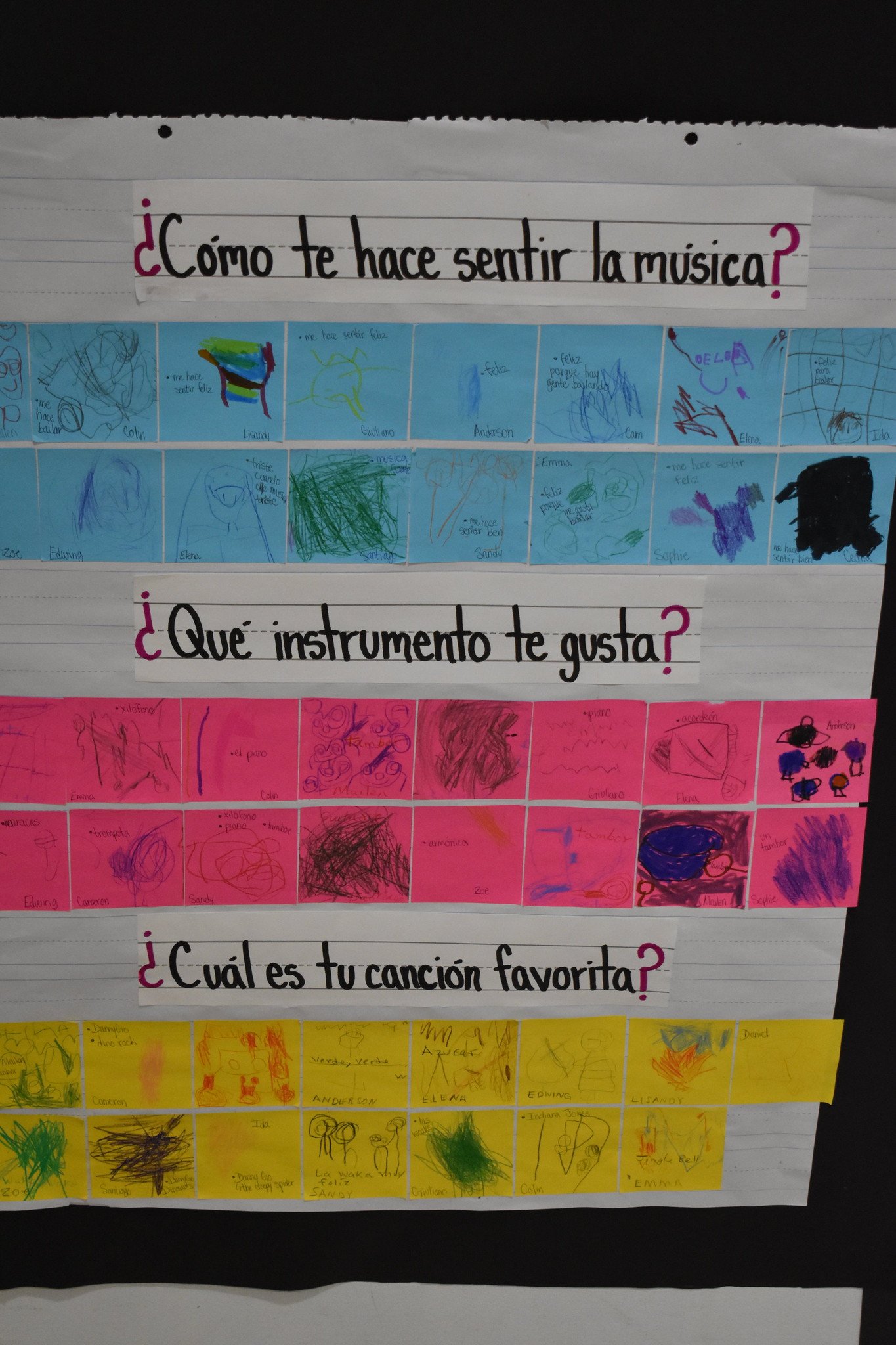

The pre-K students studied dance and music from Central America, including protest music. Lyrics were on the wall from a song called “Queremos Justicia” and there was a huge wall of pictures entitled “Aprendiendo Centro America a Traves de la Musica” and another on “My Musical Identity.”

They also made a dish of beans, corn, and squash that was given out in the hallway with chips as part of their garden program.

Event Program

Here are some of the questions the pre-K students explored.

What differences are there between our music and Central American music?

What differences were found in the U.S. national anthem and Centro American anthems?

How do people from Central America celebrate?

How do Central American people protest?

Kindergarten

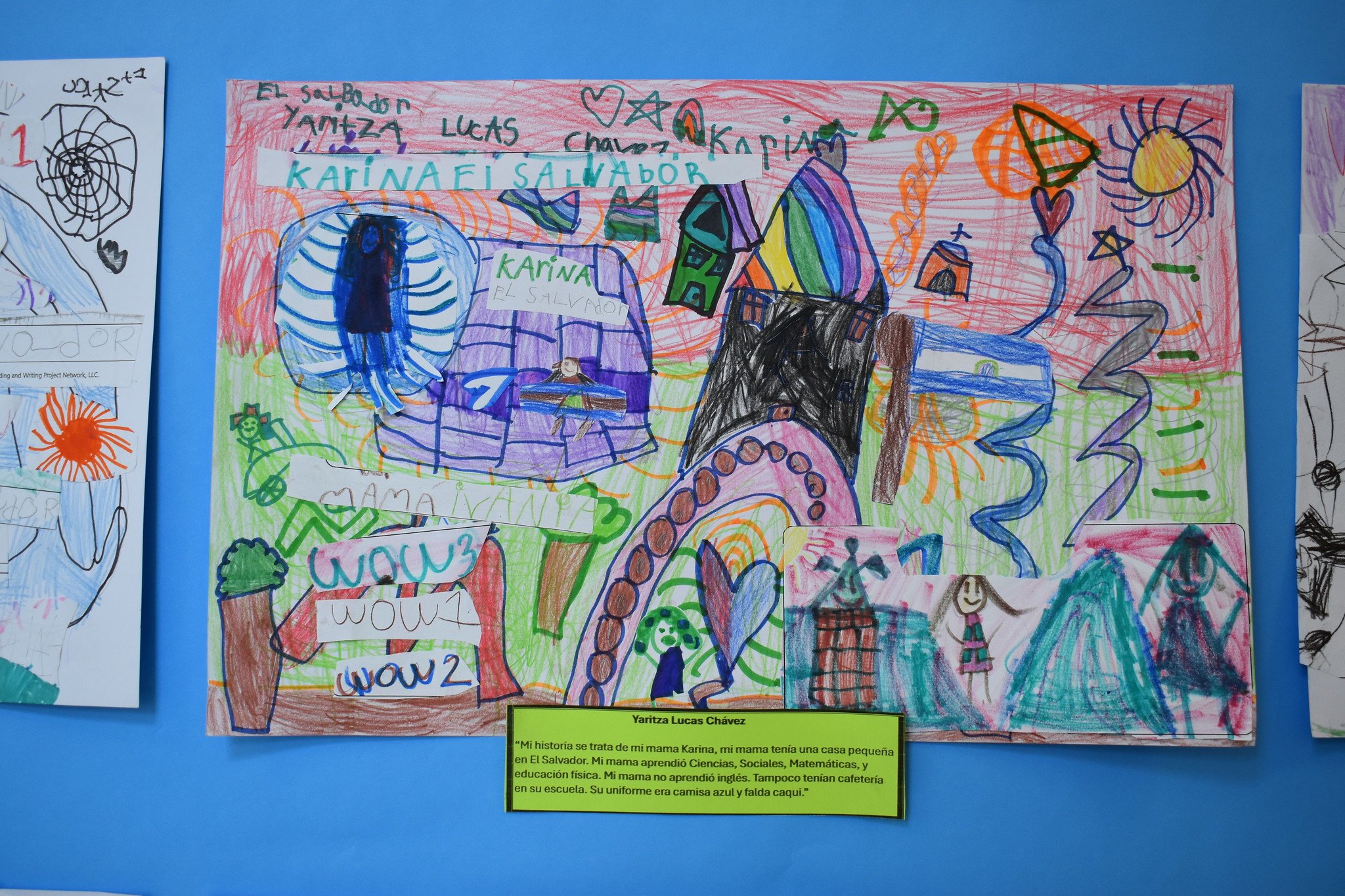

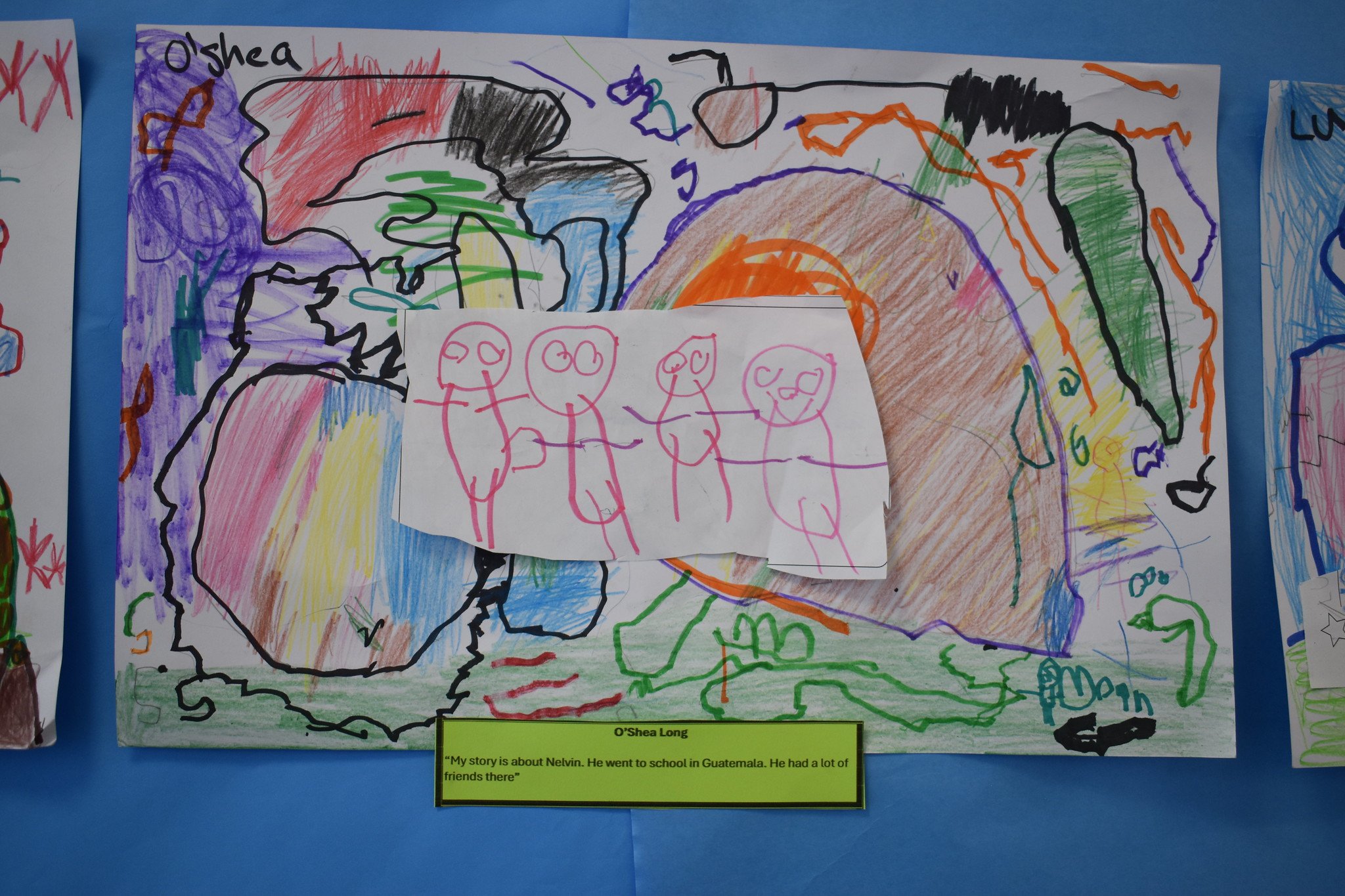

This class created posters about two Central American artists: Salvadoran Fernando Llort and Guatemalan Margarita Azurdia. They also created little passports, banderas (flags) de identidad, and wrote stories about fellow students and staff from Central America.

Event Program

Students retold stories based on in-class interviews from families and staff members sharing their experiences of going to school in Central America. To deepen our understanding of the different experiences, we dedicated four weeks with intentional learning routines to merge all the information learned into one final product. Students created artwork retelling the stories about Central America.

Week 1: Discovering Central America

Week 2: Stories about Central America

Week 3: Retelling stories

Week 4: Reading the world

1st Grade

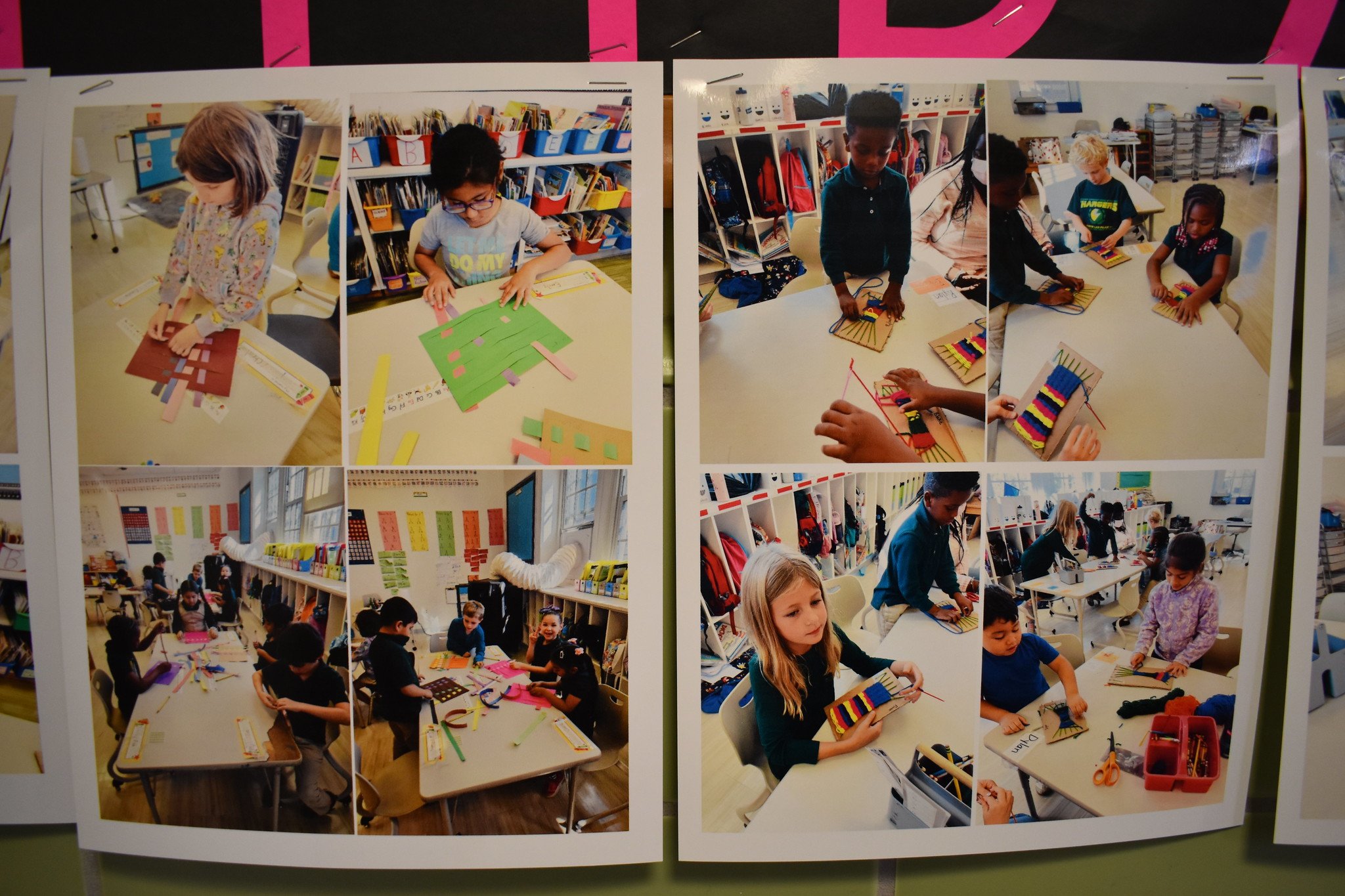

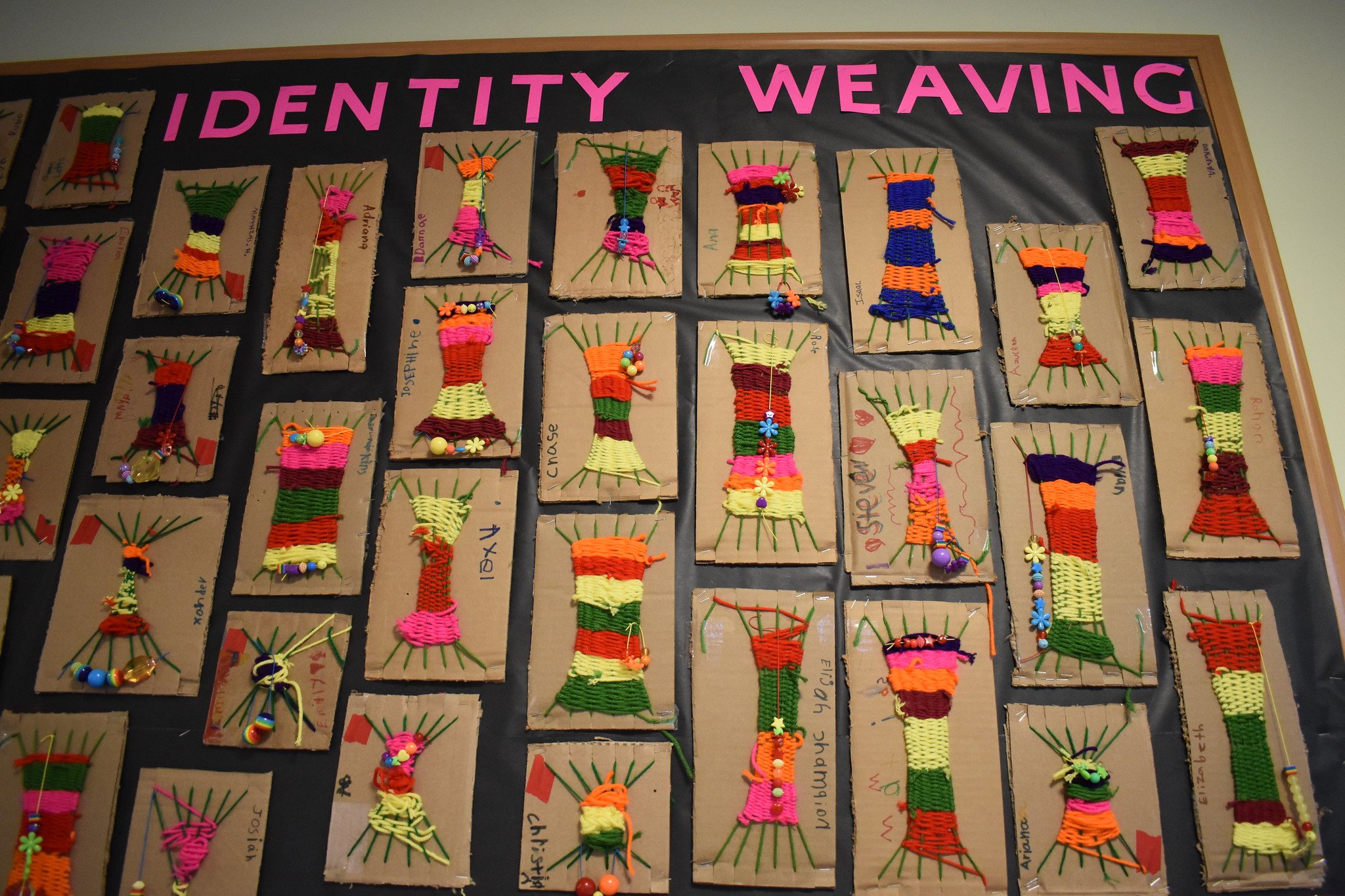

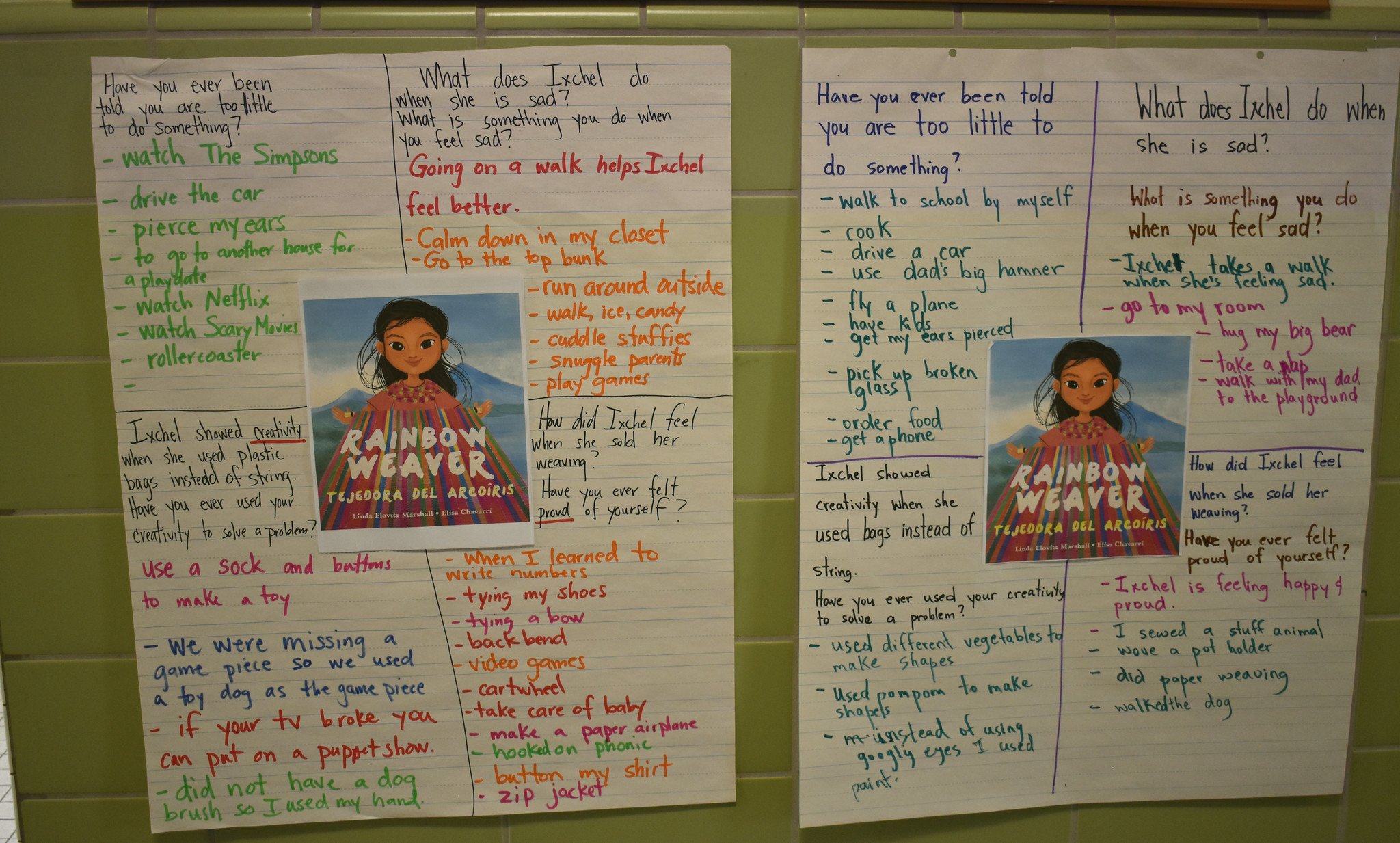

The 1st graders studied the way in which generations pass down stories and skills. They read Rainbow Weaver, a bilingual picture book about a young girl who learns the traditional weaving style of Guatemala. Students made their own weaving projects, using colors to connect to different parts of their identities. They connected this work to their science study of genetic inheritance of traits and how they are passed down through families.

Event Program

What shapes my personal identity?

How is physical/cultural identity passed down?

We all are uniquely ourselves, weaving together parts of our identity to understand who we are. In science, 1st graders learned about how physical traits are passed down generation to generation. After reading the poems in the 1619 Project’s Born on the Water, they further explored personal and cultural identity by asking:

o Which parts of our identity change throughout our life?

o Which are parts that come from our family? Which are unchangeable?

o What is your social identity? What is your racial identity?

With a focus on Teaching Central America, 1st graders studied Mayan art and weavings from Guatemala. Classes read Rainbow Weaver and learned how Ixchel used weaving, a tradition she learned from her mom, to help her family and community. For the celebration, students displayed weavings, self-portraits, and the bands of identity that we weave together to see how we are unique. Visitors were encouraged to “add a piece of yarn to show one of YOUR strands of identity and be a part of our community weaving.”

2nd Grade

Students compared Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples’ Day. They displayed their insights on a display called “Columbus and the Issue of Colonialism as Studied and Understood by the 2nd grade.”

They also created four dimensional maps that started with their own classroom, then expanded to D.C., the world, and Central America. The 4th graders visited to study them, carrying clipboards and filling in the “themes” they noticed.

Event Program

Mapas: identidad y criticidad/ Maps: Identity & Criticality

Students began the year exploring different parts of their personal and social identities as inspired by our 1619 Project work and the book Born on the Water. The students authored bilingual “Identity Books” reflecting their language identities, their values, and important people and places. Displayed also were our “Figure Me Out” math identity posters, Heart Maps of students’ hopes and dreams for 2nd grade and Name Acrostic Poems. Please make sure to see our charts that show what students know about Identity, Culture, and Values to see how we completed our books.

In social studies, students learned about map features and the difficulty of accurately representing a spherical Earth on a flat map. We asked, “Where are we on the map?” Our Map Mobiles represent all the places we belong (our classroom, our city, our continent, and our world). The big question we asked when these projects were completed was: “What are our roles and responsibilities as members of each of these communities?”

Our map study continued with a focus on Central American countries. Students worked in groups to research and present important information about a country of their choice, studying its flora and fauna, geography, population, and weather. We also studied “official” vs Indigenous languages in both classes. We asked, “Why does our research say there is only one official language of these countries (Spanish), when there are many Indigenous languages spoken, as well?” We had a visit from Kevin’s parents who shared about their languages and also about Guatemala’s independence movement. We asked, “What is the connection between independence (“saying goodbye to Spain,” as they explained) and Indigenous culture and language.

Though we are at the beginning stages of studying and understanding Indigenous cultures in North and Central America (we go on a field trip tomorrow to continue this work!), we learned the words INDIGENOUS and ACKNOWLEDGEMENT. Due to the timing of Teach Central America and Indigenous Peoples’ Day, we considered the questions, “Should we celebrate Columbus Day or Indigenous Peoples’ Day? Why?” and “How does this connect to our 1619 Project work with the book Born on the Water?”

We gratefully acknowledge the Native People, specifically the Nacotchtank, Piscataway, and Pamunkey, who were the first inhabitants of the D.C. area. We also acknowledge the Indigenous people of Central America who continue to live in their native homes and those whom have moved to the D.C. area and make up a large and vibrant part of our BMPV community.

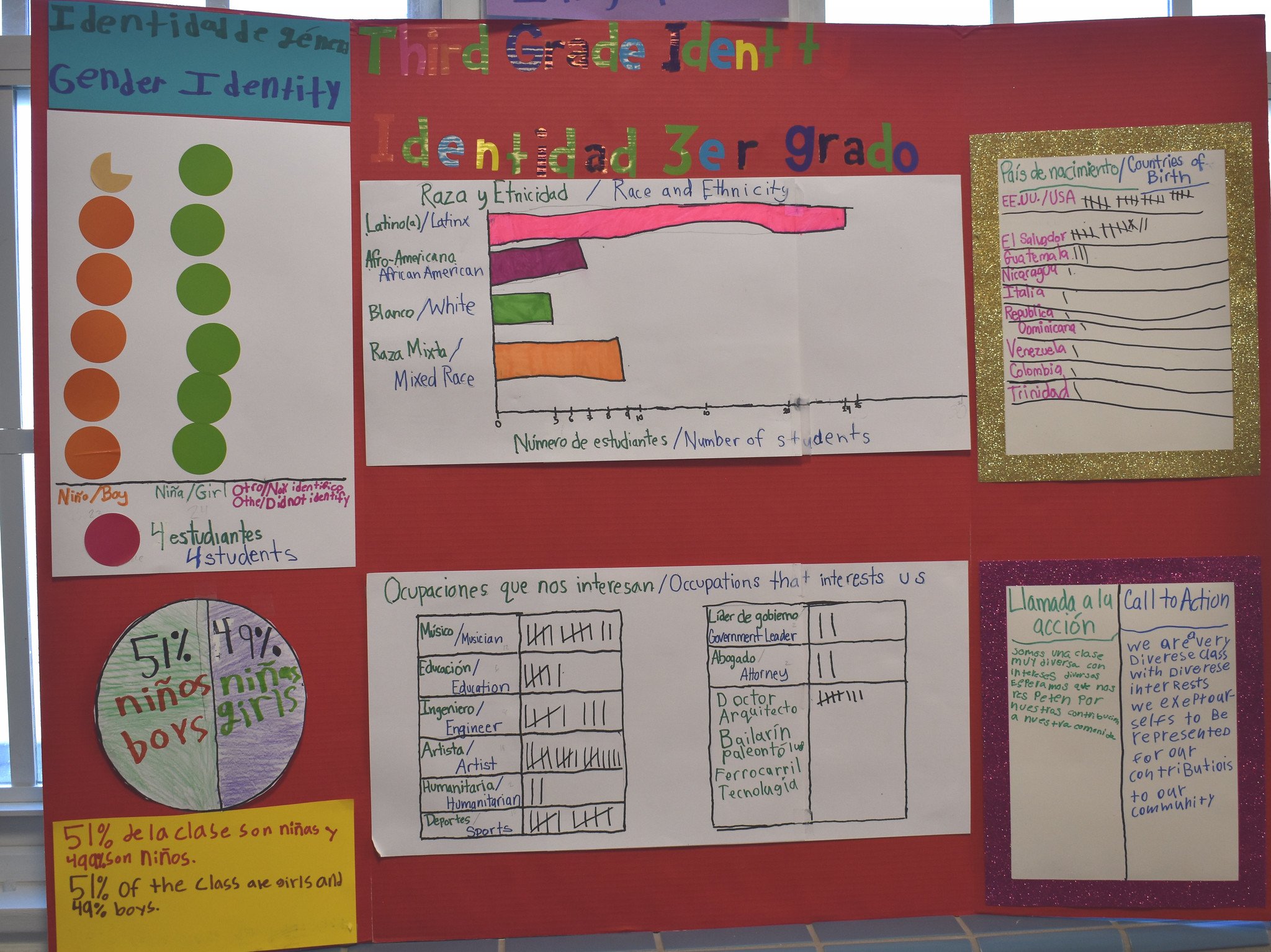

3rd Grade

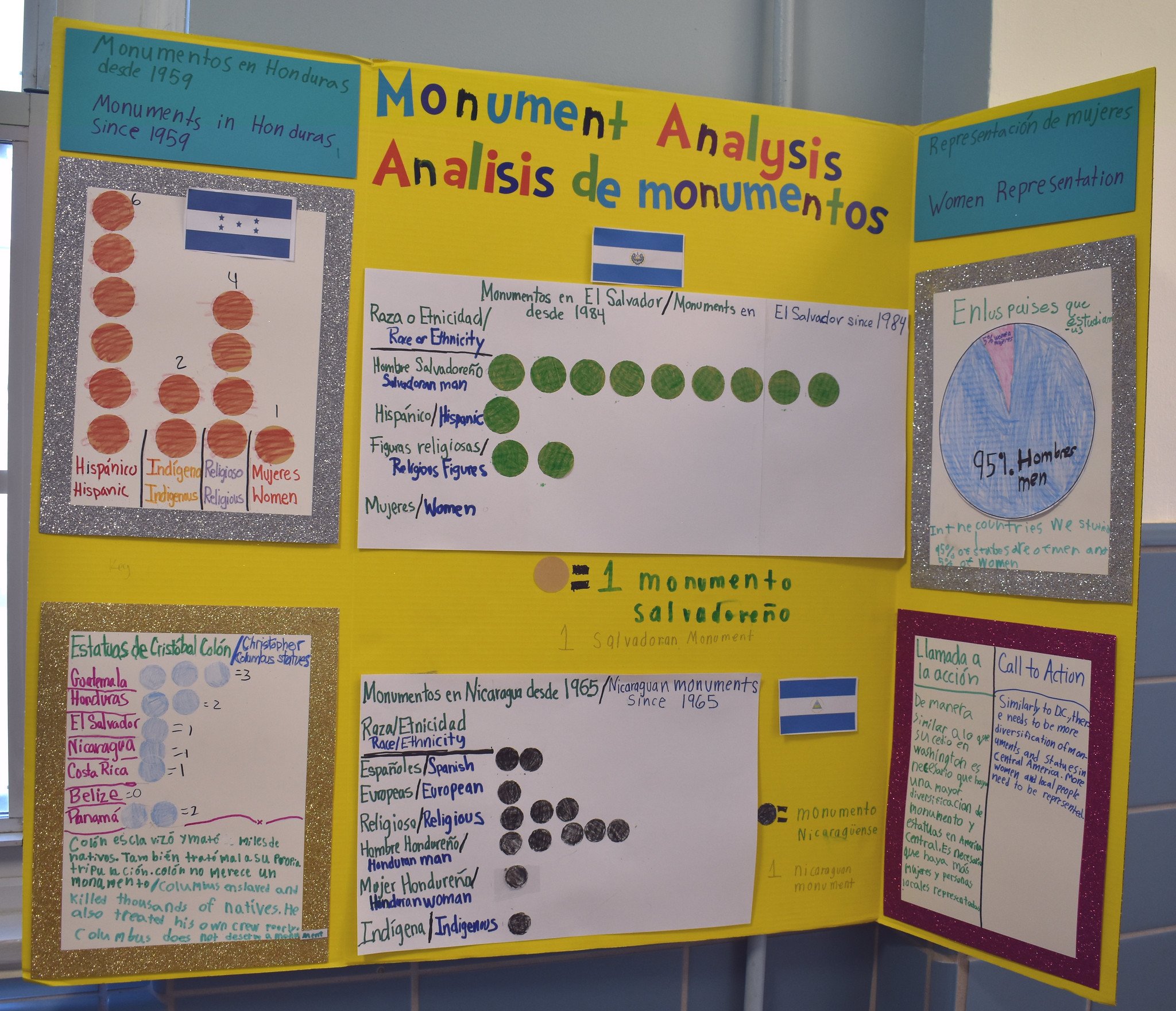

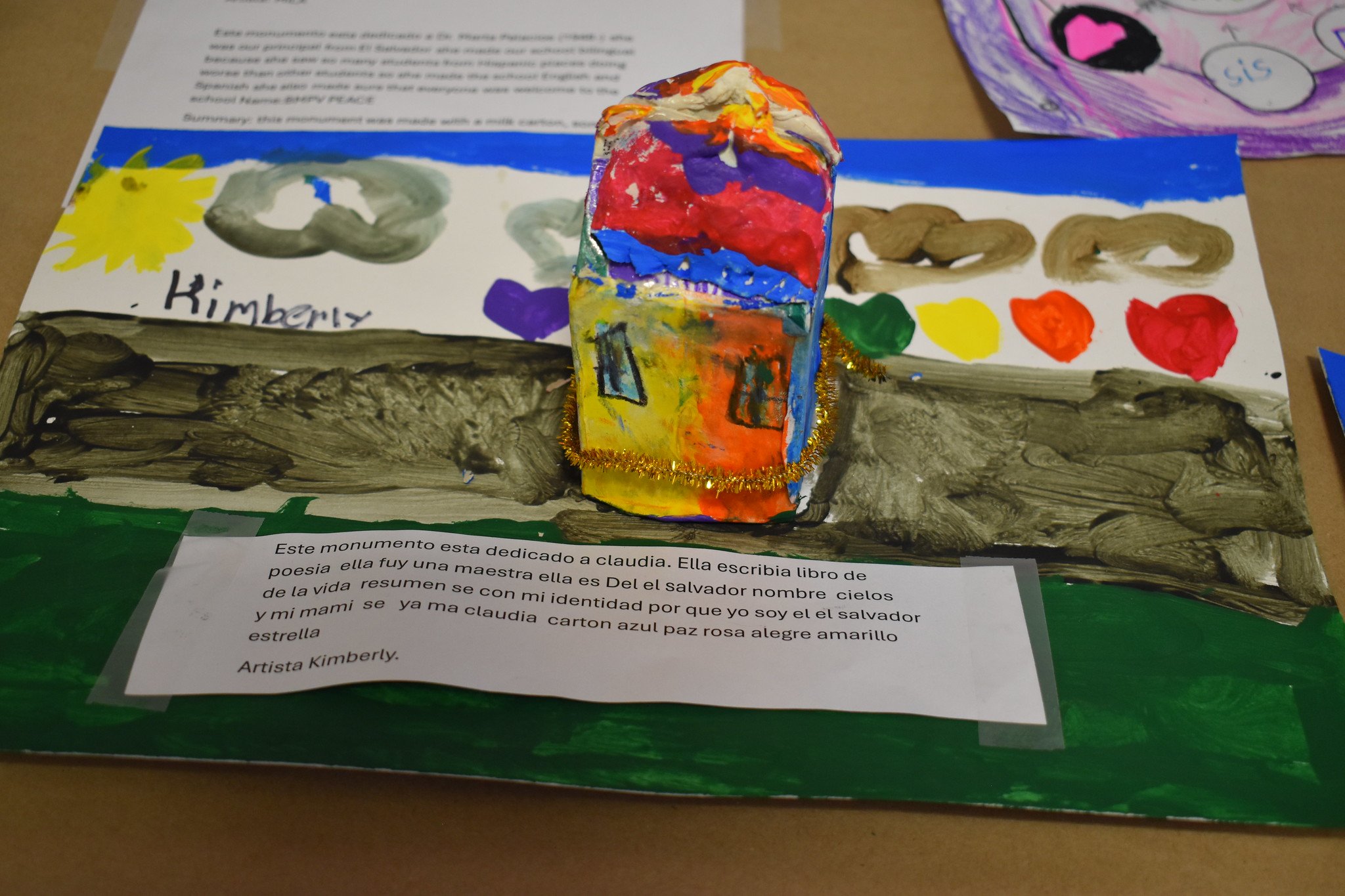

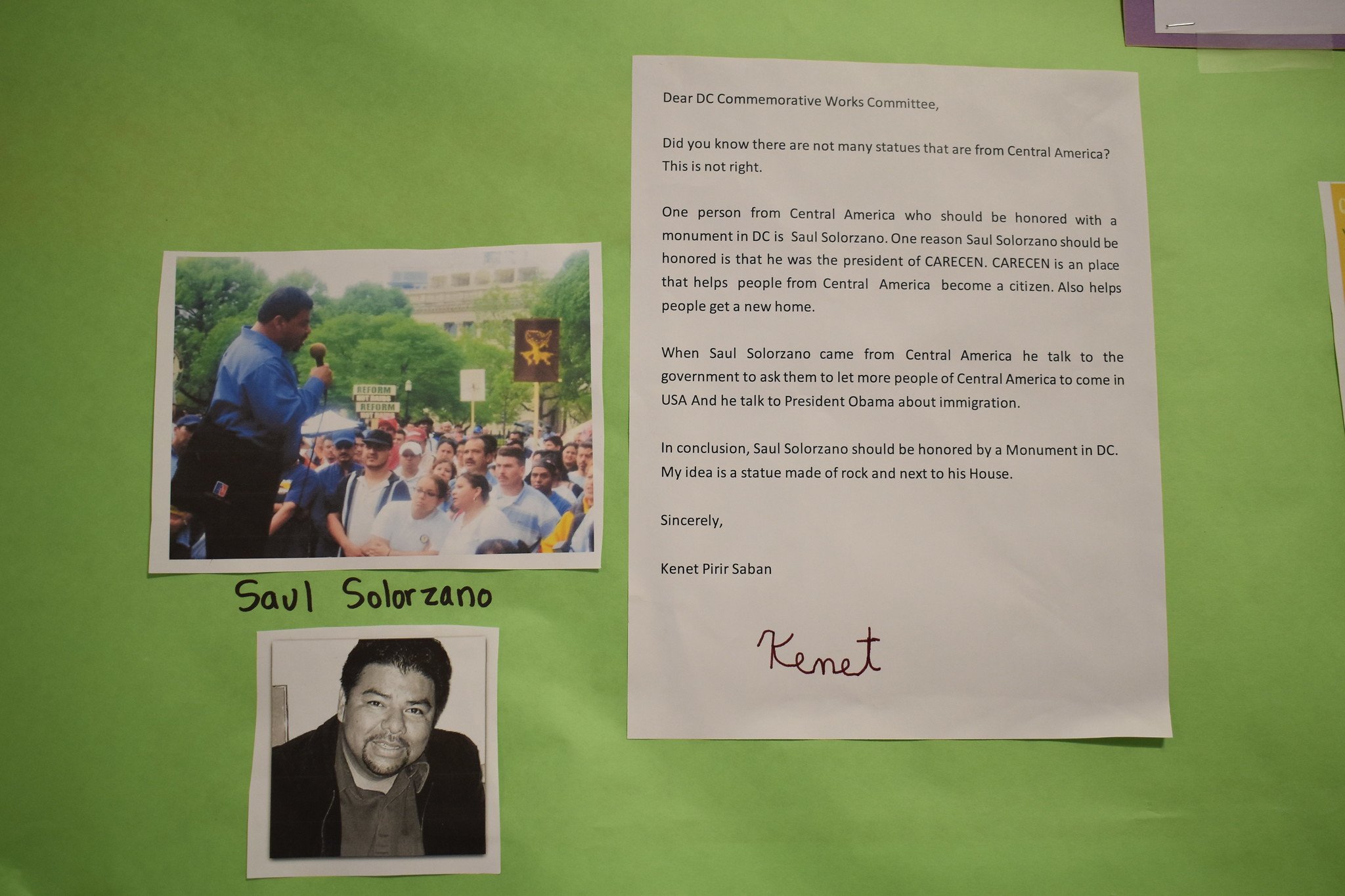

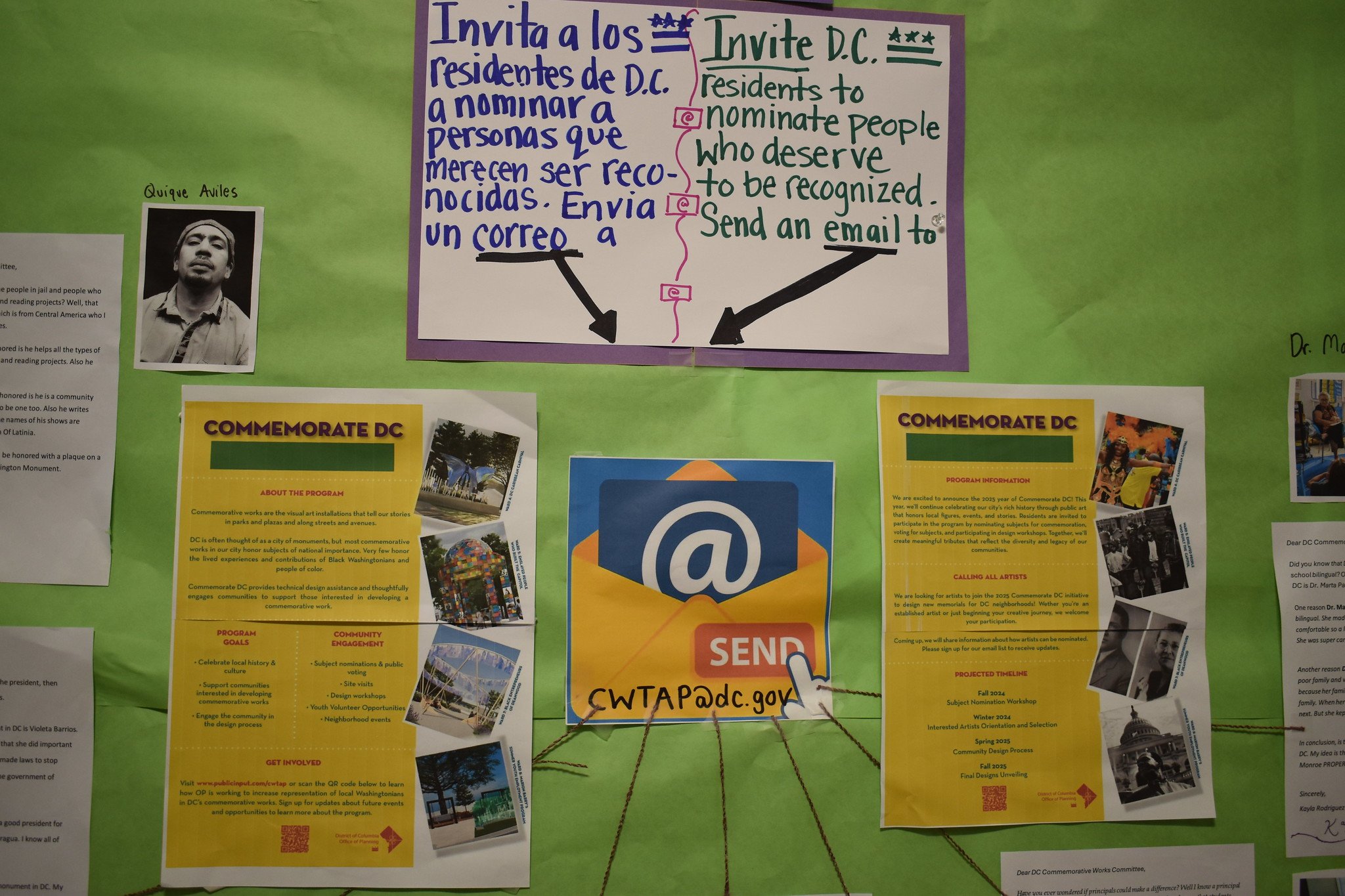

Their theme was who deserves a monument. They traveled around D.C. to look at monuments and came up with some data showing most of the monuments in the city recognize white men. They shared their findings on a poster and graph: 42 monuments were of white men, three were African American, three were Hispanic, two were Indigenous, and 0 were Latino. Forty were men and five were women.

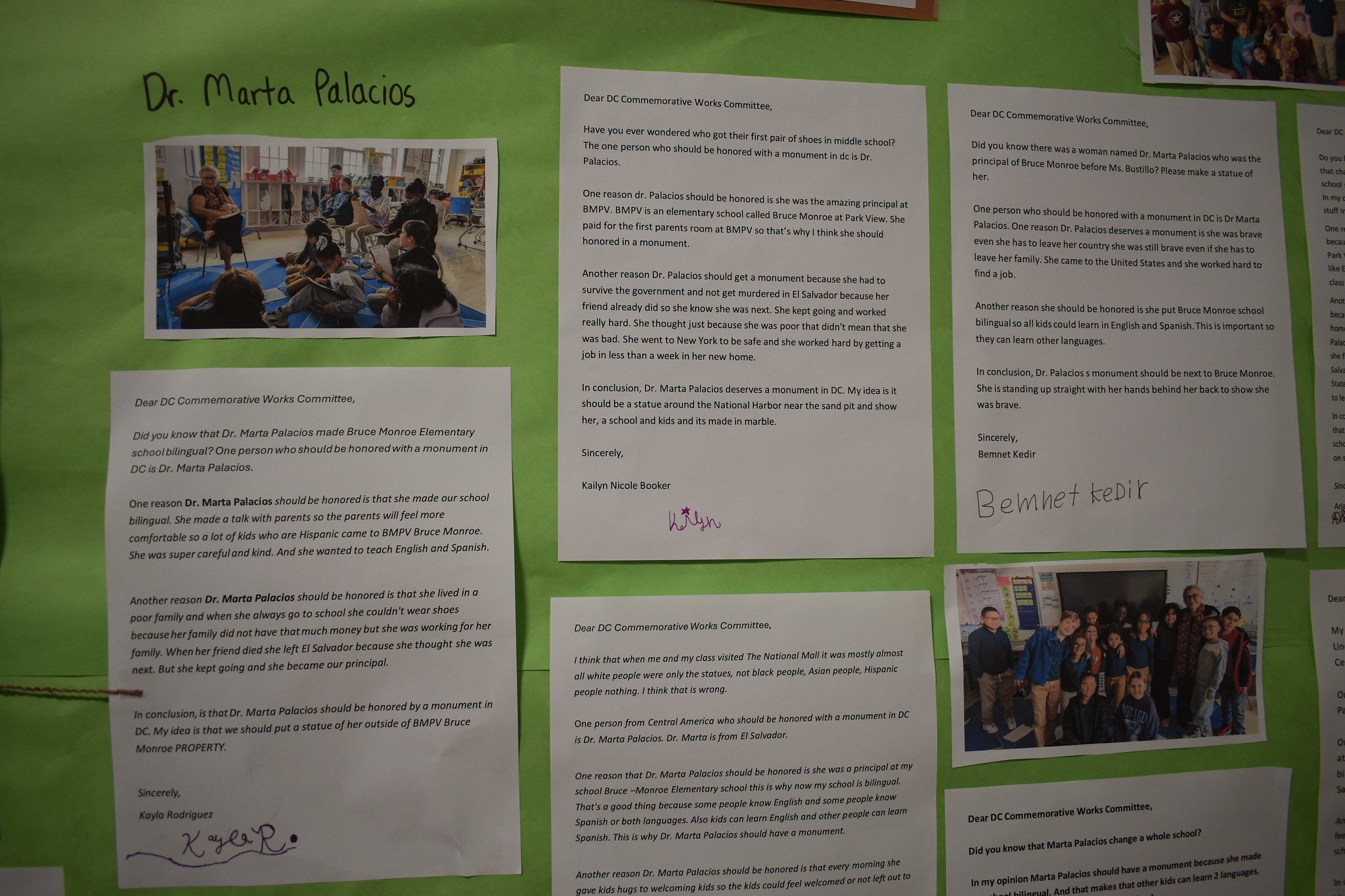

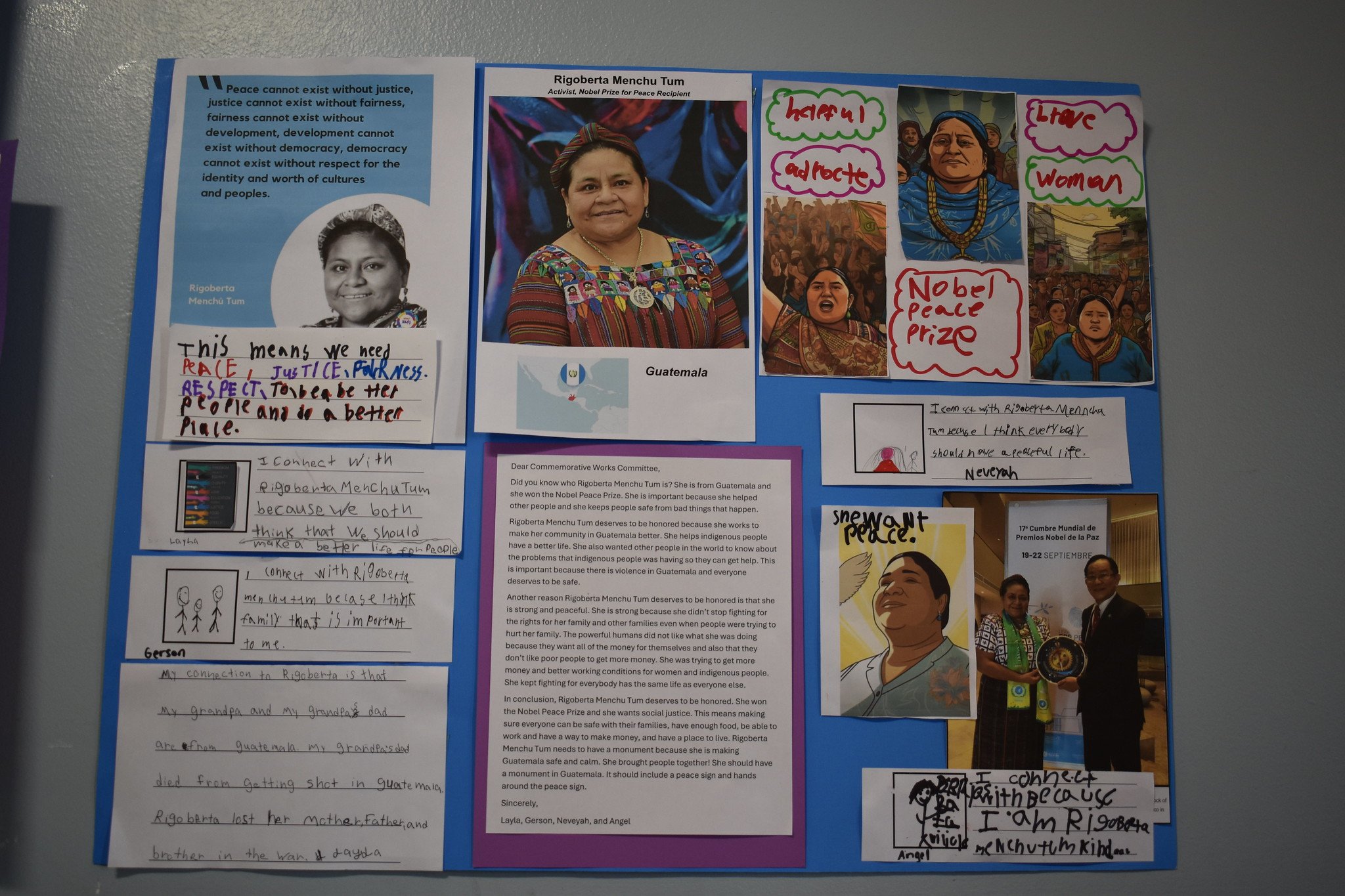

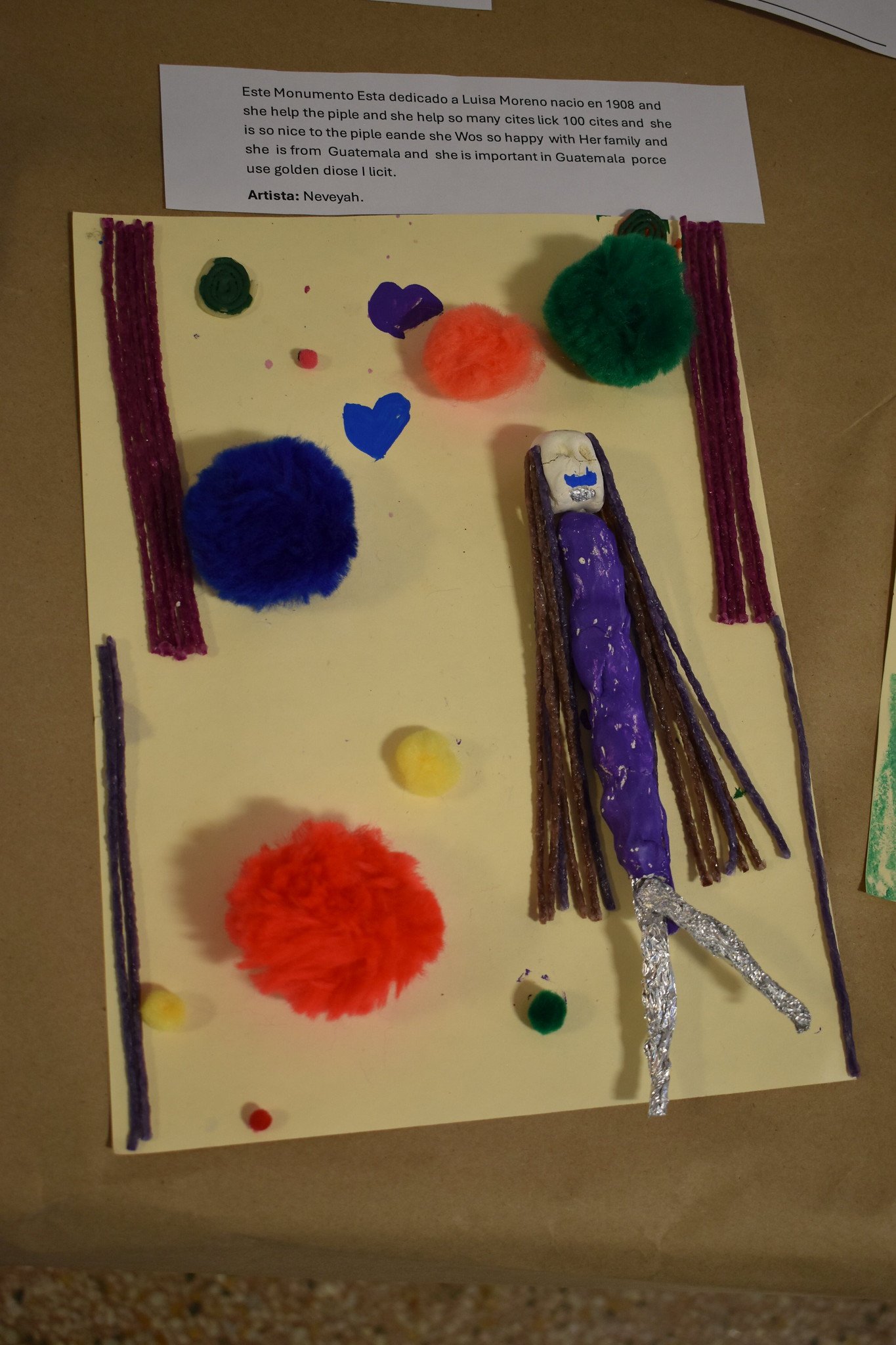

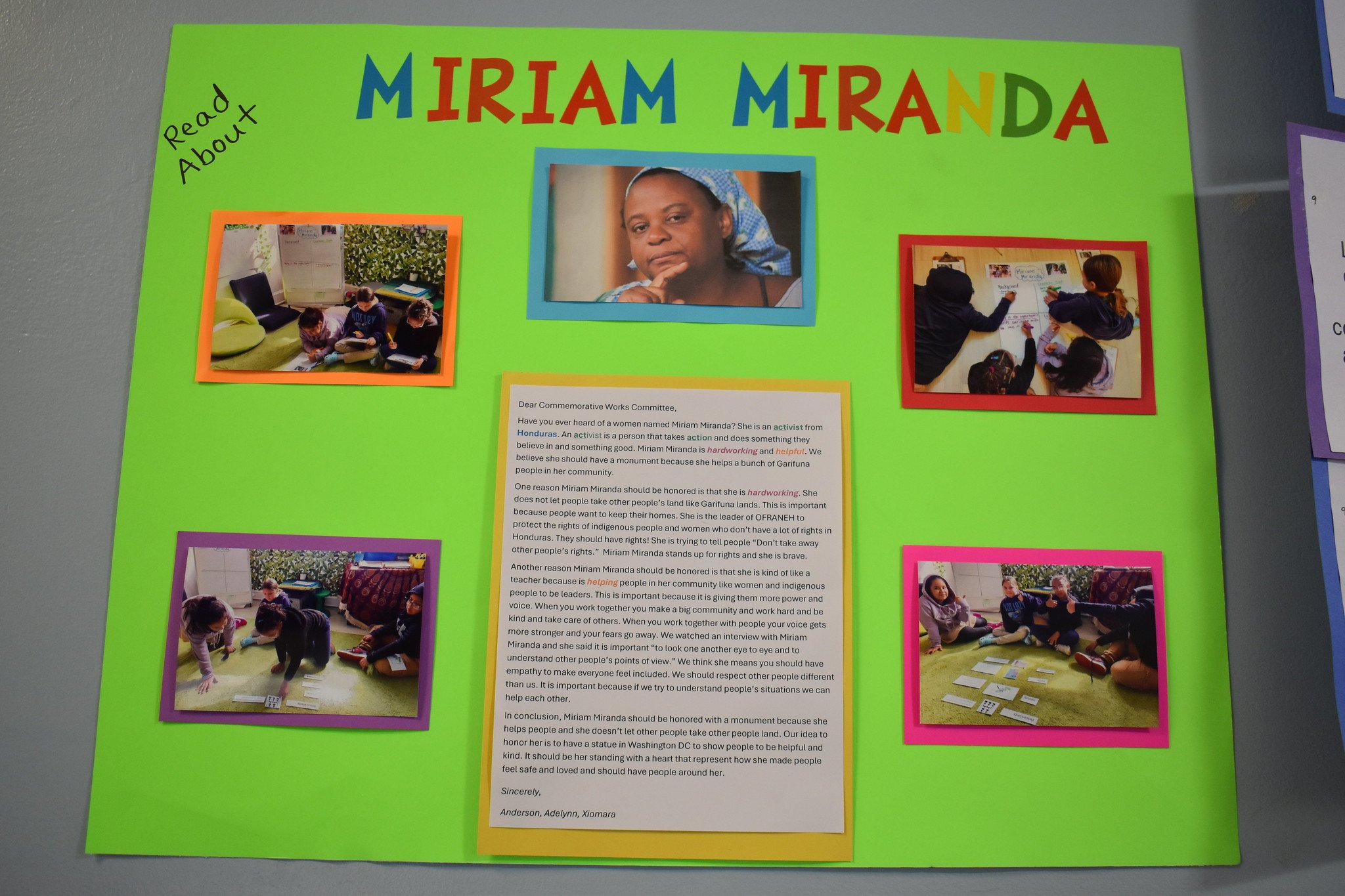

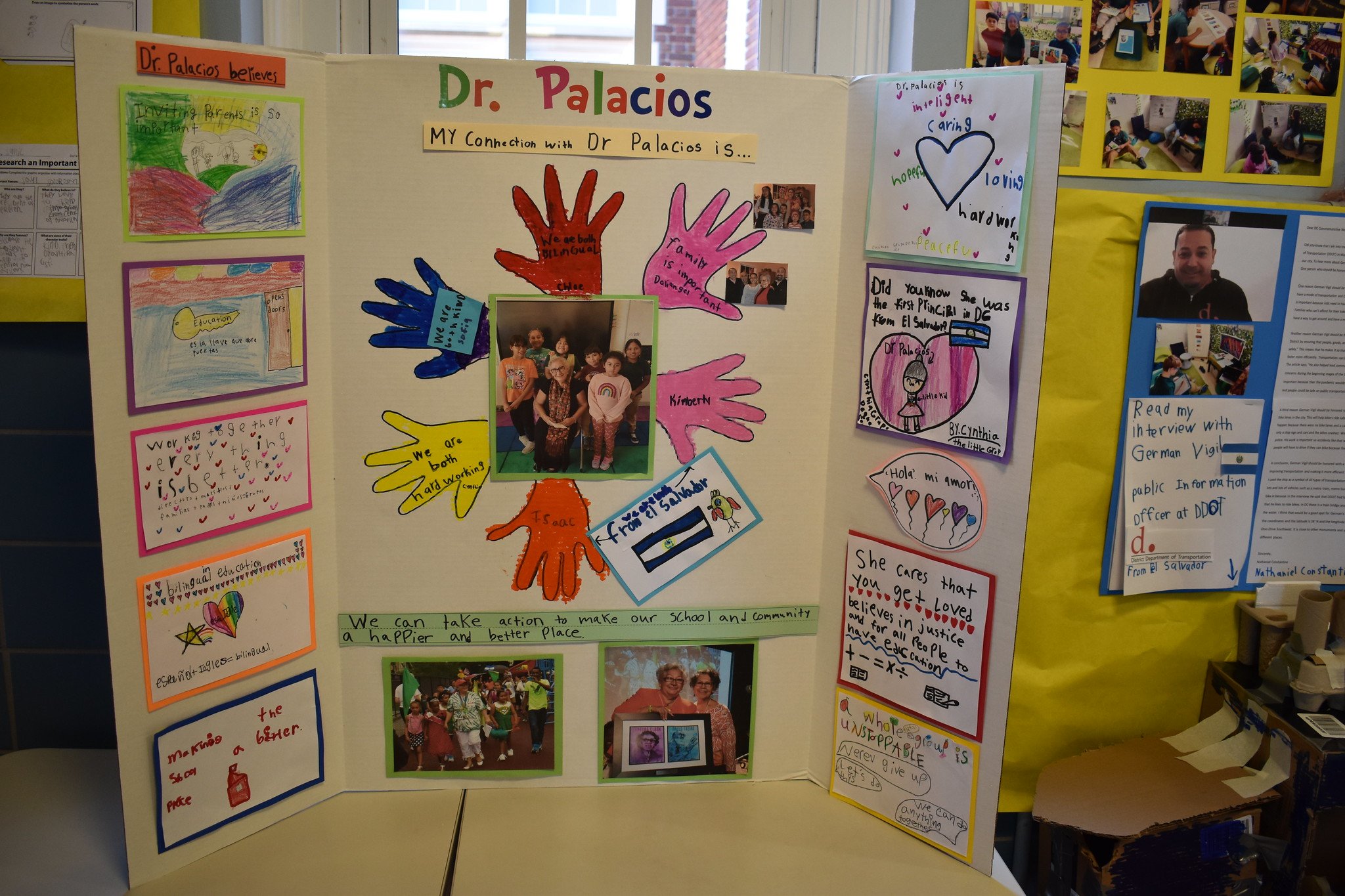

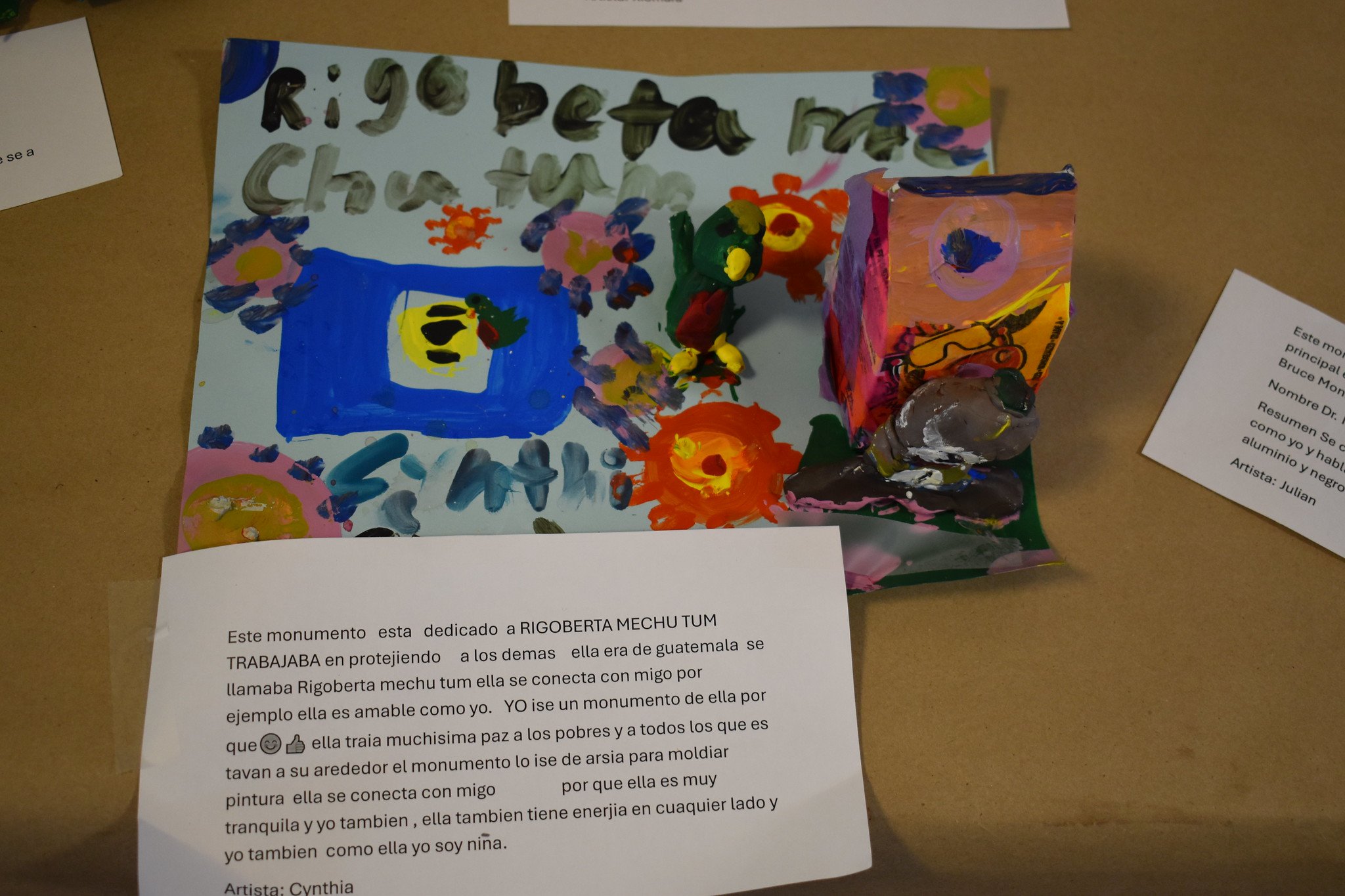

Using a research form, they collected information about someone they considered to be person who should be recognized. From there, they made small artistic tributes to that person and came up with recommendations of which people they thought should have a monument. Those got a poster with a picture (photo or drawing or both) and a narrative about them. Their recommendations included:

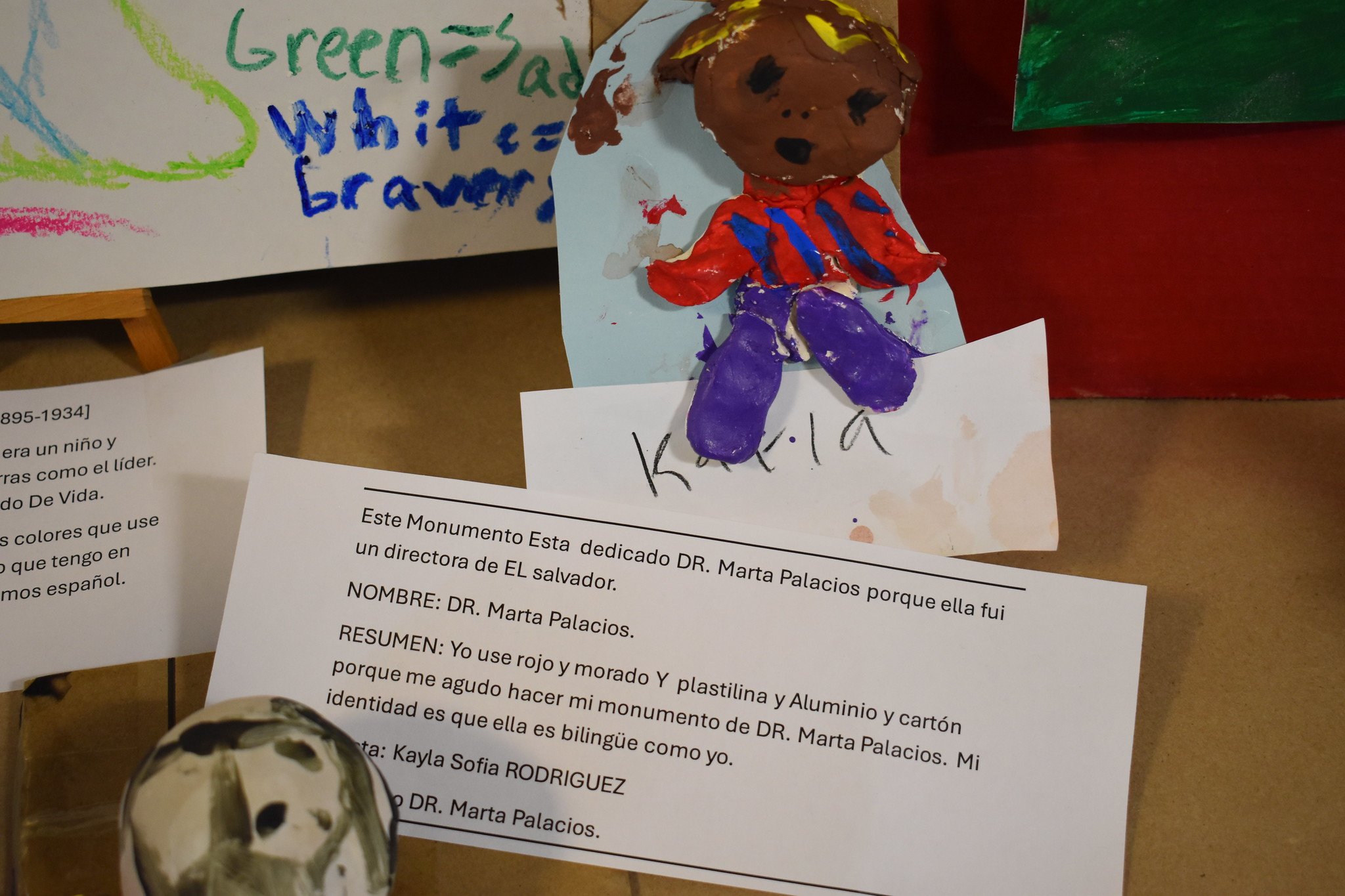

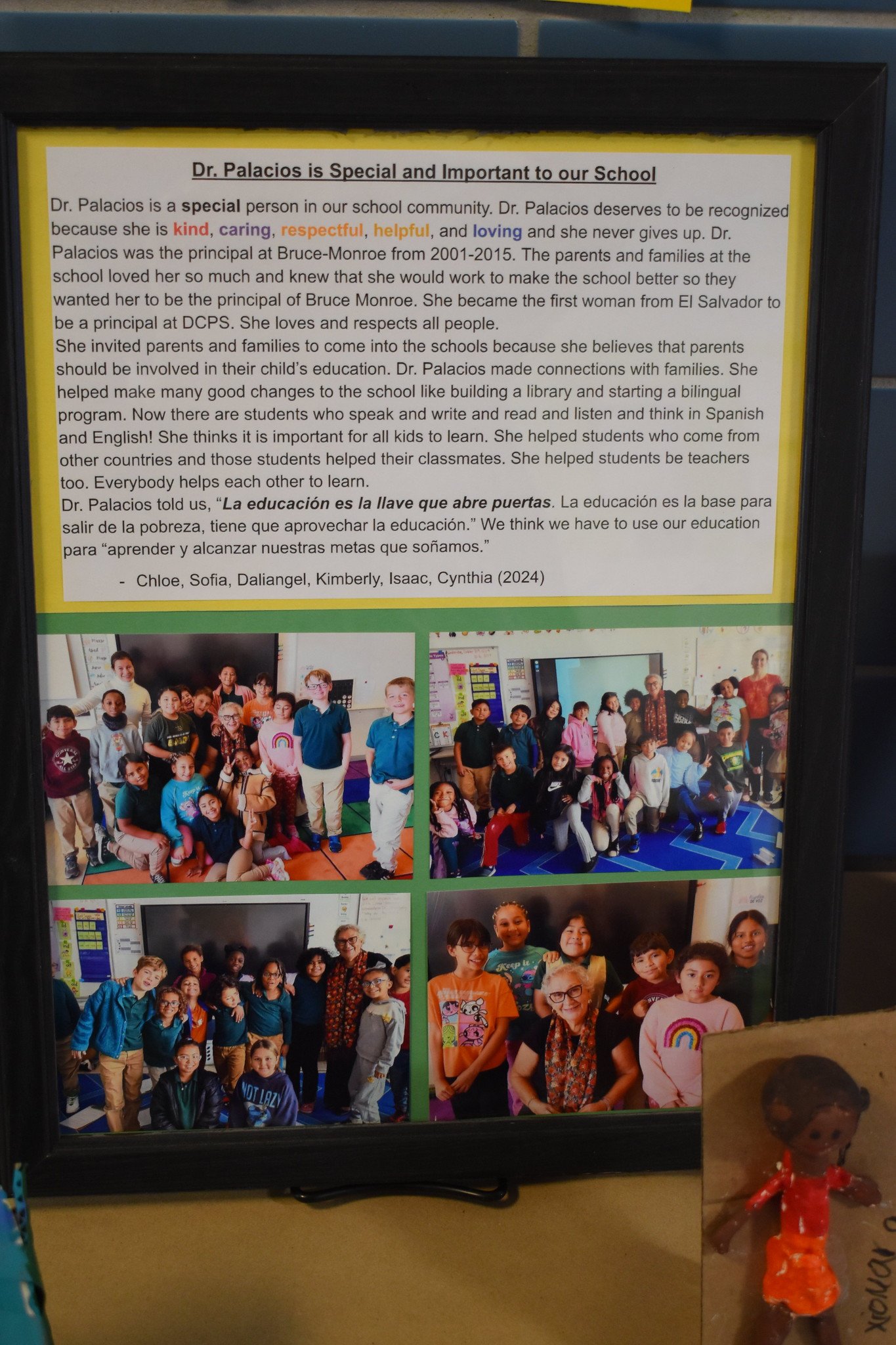

Marta Palacios, previous principal of Bruce Monroe who turned it into a bilingual program. Students met and interviewed her.

Lupi Quinteros-Grady: director of the non-profit Latin American Youth Center

Prudencia Ayala: A woman writer who ran for president in El Salvador in 1913.

Quique Aviles: local artist and performer

Rigoberta Menchu: Guatemalan leader representing the Indigenous community

Violeta Barrios: former president of Nicaragua.

They wrote letters to the D.C. Commemorative Works Committee to advocate for each individual they recommended.

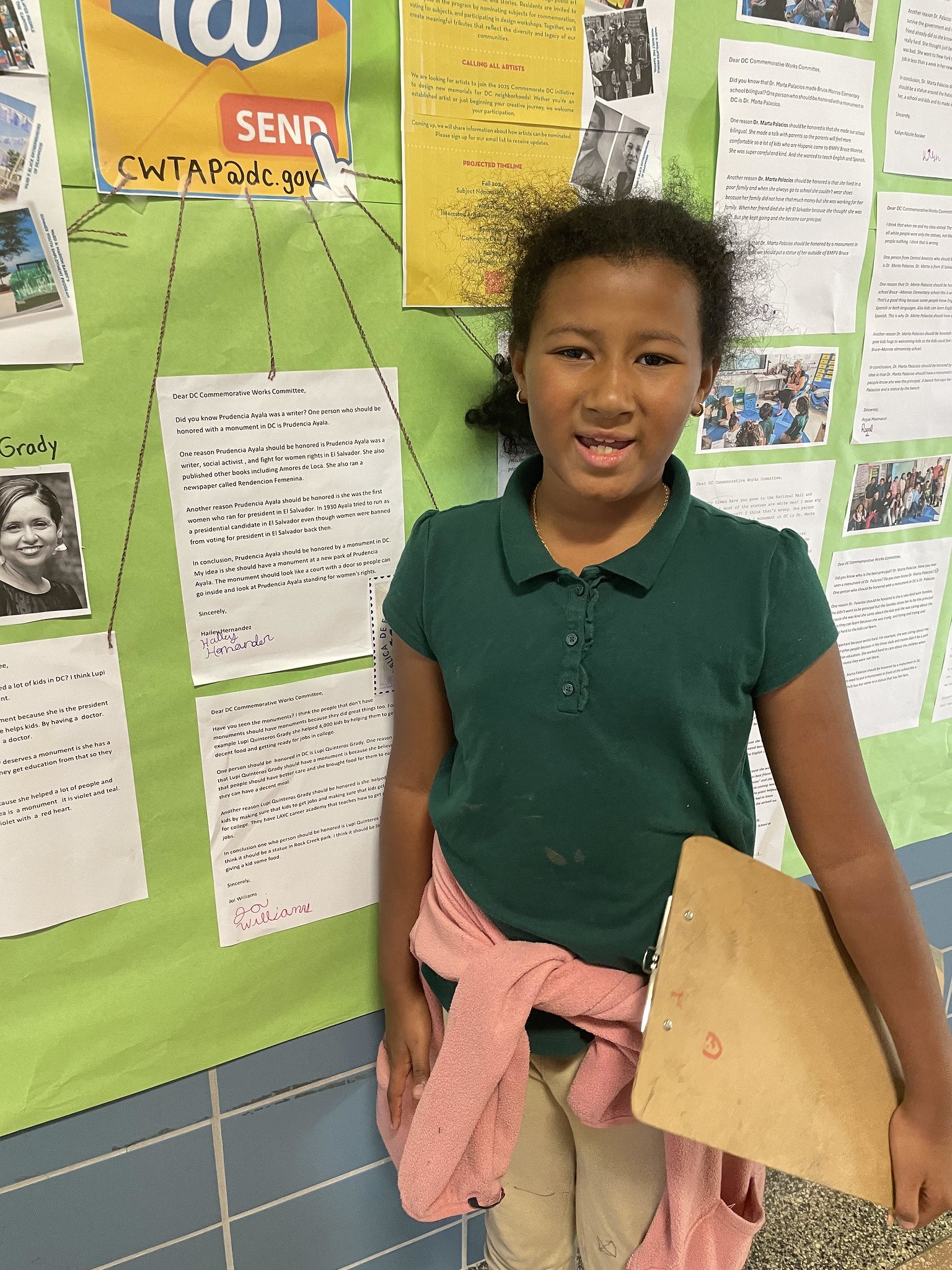

Three of the students and their recommendations are pictured below. Melody recommended Lupi Quinteros Grady receive a statue, Chloe recommended Dr. Palacios because she “fixed up the school, built a library, made the school a better place, and made it bilingual,” and Hailey recommended Prudencia Ayala.

Students created a bilingual “Call to Action,” saying: “Similar to D.C., there needs to be more diversification of monuments and statues in Central America. More women and local people need to be represented.”

They also created a chart with the demographics of their class.

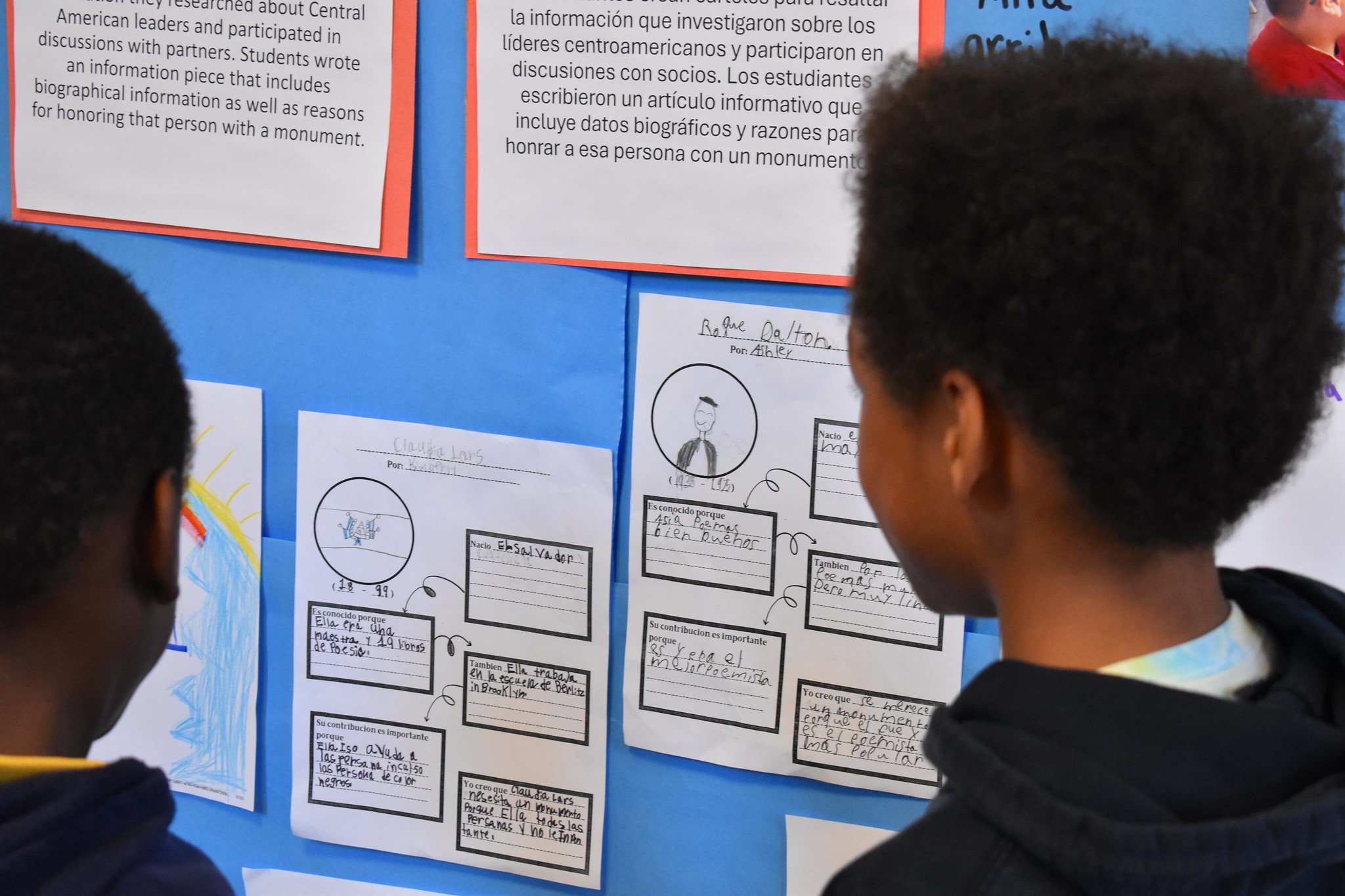

Event Program

Who is represented and not represented in our monuments?

Who are influential leaders in or from Central America?

Why and how do these leaders deserve to be honored?

Students began by exploring aspects of their own identities and noticing connections with classmates. We read and discussed news articles about the lack of diversity in public monuments in DC and across the U.S., and we visited major monuments in person during a field trip to the National Mall. Students questioned why most of the monuments are of white men when there is so much diversity in our class and community.

We also learned about local efforts to build more diverse monuments and memorials in D.C. but noticed that people from Central America are still not being honored. Therefore, we decided to research local community leaders who are from Central America. We wrote opinion letters to the DC Commemorative Works Program to share our ideas for who deserves a new monument or memorial.

Students also did research on different leaders from Central America to reflect on why their contributions are important and analyze whether they deserve to be honored. Students created posters to highlight the information they researched and participated in discussions with partners. Students wrote an information piece that includes biographical information, as well as reasons for honoring that person with a monument.

Students incorporated math skills to make identity pages and create different infographics to summarize their research.

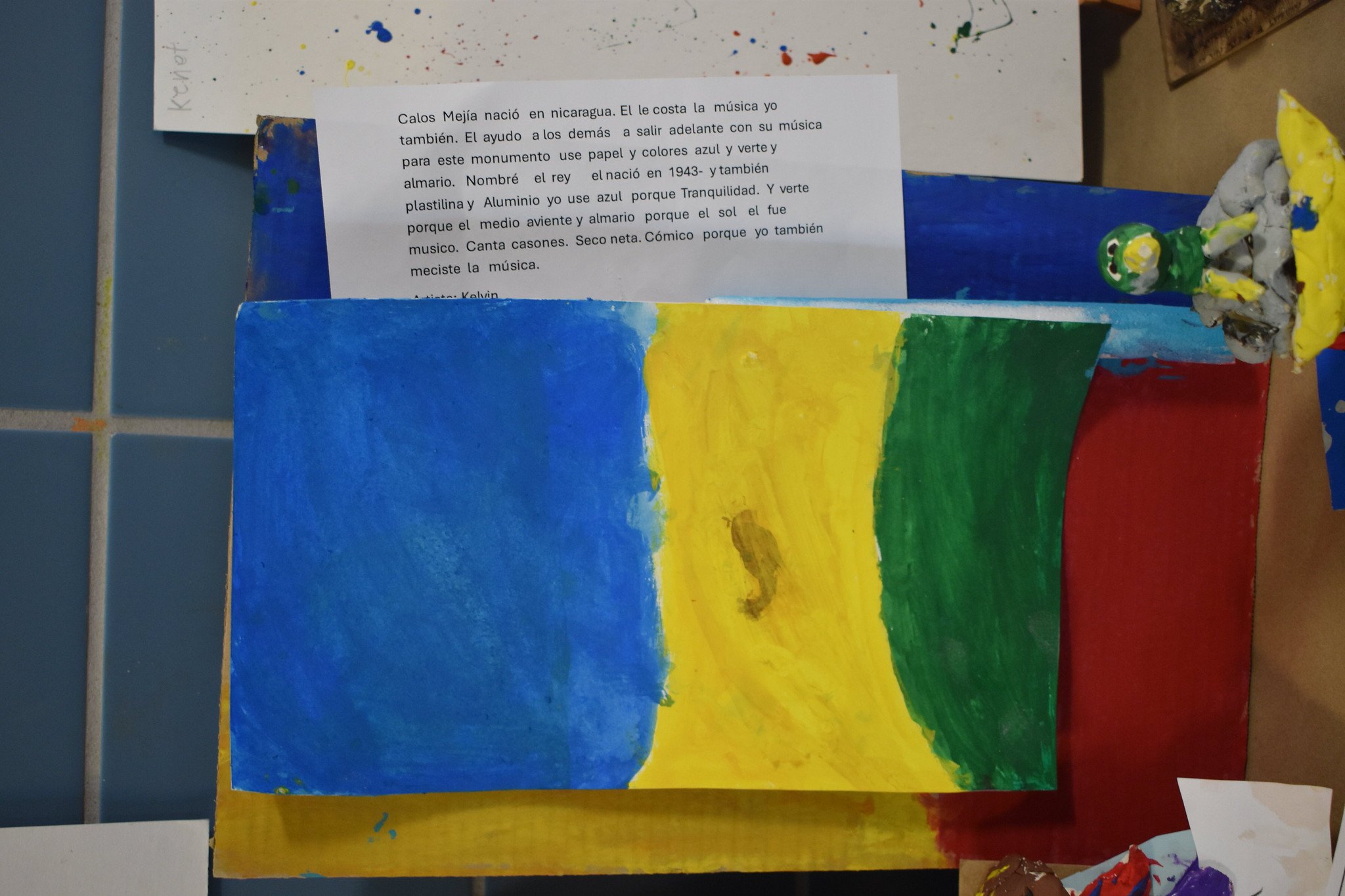

As a culminating project, students created their own monuments to one leader they studied.

4th Grade

This class looked into nature. They drew trees, such as the Arbol de Ceiba and its characteristics.

They also looked at the similarities between Central America and Africa in terms of colonization, slavery, and loss of language. They drew maps and listed all the languages spoken both within Guatemala and also throughout Africa.

One of their assignments was to look into animals from Central America. Jocelyn, who is of Mexican and Salvadoran background, did research on the ocelot and created a website about it. Another child, Daniela, of Salvadoran background, studied the brown-throated sloth and created a website about it.

Event Program

What are some of the representative plants and animals of Central America?

What importance do they have in the culture and identity of the inhabitants of this region?

What connections can I make between my heritage and the natural elements of this region?

How do organisms adapt to survive? What connections and inspiration can we gain from the natural world? What significance do the plants and animals of Central America hold for both the ancestral and modern peoples there? Fourth-grade students investigated these questions through their studies in reading, writing, and science.

Students read realistic fiction books and studied how internal and external character traits show that people are complicated, not one dimensional. Students deepened this thinking while reading about a Guatemalan forest protector in Margarito’s Forest and a boy who emigrates from El Salvador in Wilfredo.

In science, the 4th graders studied the internal/external features and adaptations of plants and animals, connecting this to their study of characters and their own identities.

Students noticed that in the same way each part of an ecosystem is unique and crucial, we each bring something special and important to our communities. The final product was an interactive forest that teaches the audience about Central American organisms while building connections between organisms’ scientific traits, Indigenous cultures, and students’ identities.

5th Grade

The 5th grade class studied the concept of change. They read The First Rule of Punk and connected the character’s exploration of her identity to their own personal narrative stories. Then they studied Mayan culture and science, by researching the Mayan concepts of the sun, calendars, and seasons, connecting Mayan and modern scientific knowledge to the theme of change. Students then put together their learning into a zine, based on the zines created by the main character in The First Rule of Punk.

Event Program

How do we change over time? How do we know if we’re progressing?

How does knowledge of the world change over time? Does progress benefit everyone equally?

Fifth graders will be engaged in a year-long inquiry of fact versus fiction, exploring how knowledge changes over time and ideas become outdated. This year in PBL, students will examine U.S. history through this critical lens. In reading, writing, and science, the same was applied to personal identity and growth: How have WE changed over time? Who do WE WANT to be?

Students wrote small moment stories reflecting a lesson they learned or a time that changed them. In a novel study of The First Rule of Punk, students discovered how the primary character Malu changed over time, becoming the imperfectly unique and best version of herself.

Through the Science Unit 1: Observing Our Sky, students learned about key 21st-century scientific principles of the sun and planet Earth. Centering Central America, students explored: How did the Maya understand time and space? What were the contributions of Mayan civilization to modern astronomy? Using a website created by Indigenous Central Americans and supported by the Smithsonian Native Knowledge 360 project, students set out to answer their questions.