A weapon developed by the Pipil or the Xincas in Guatemala. A pile of rocks is situated beneath a stick suspended by a twisted rope. When the stick is let loose, the rocks are dispersed at a high velocity. Drawing from Fuentes y Guzman in Recordacion Flo rida (Sociedad de Geografia e Historia, Guatemala)

Don Pedro de Alvarado, Conquistadore de El Salvador (Tomollo do Horrero, Decadas, Madrid, 1601)

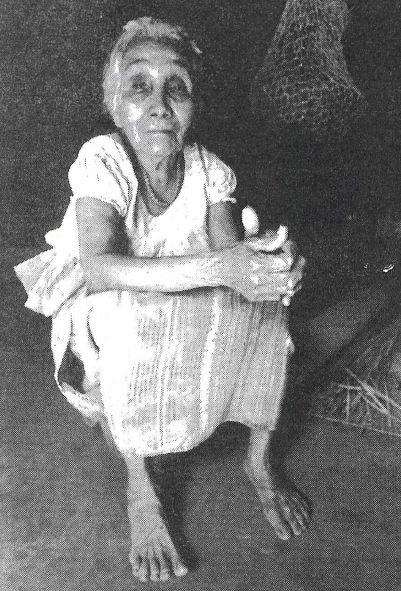

Photo: Sonsonate, El Salvador. This 90-year-old woman lost most of her family members in the Matanza of 1932. She not only survived, but was one of the few to resist assimilation into the Spanish creole culture. She speaks Nahuatl. The fabric in her skirt is from Guatemala. There are no longer weavers who make traditional huipiles or dress in El Salvador. © Donna Decesare, 1990.

By Bill Fowler

In Central America, we generally associate indigenous peoples with Guatemala. However, if you look closely, you will also see much evidence of Salvadorans' indigenous heritage. If you look at a map of El Salvador, you will find many place names of native origin, most of them having derived from the Nahuat language of the Pipils, once the dominant Indian group of El Salvador. If you listen closely to Salvadoran Spanish you will hear many words that derive from the Nahuat dialect. Knowledge of herbal medicine is strong in El Salvador, and this art comes from pre-Columbian Pipil practices. Traditional agriculture is widespread and based on Indian techniques. Obviously, the heritage of the Pipils remains strong in El Salvador.

Pre-Colonial History

In the early Colonial period, El Salvador was commonly known by the Pipil name of Cuscatlan. Its indigenous inhabitants were descendants of several groups of Mexican migrants who had migrated in the 11th century from the central highland plateau and the Gulf Coast region of Mexico via the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. They migrated to escape a series of droughts that plagued central Mexico as well as to seek better social and political conditions. They brought their place names with them when they moved from Mexico, and scholars have long noted the many parallels between Nahua place names of Mexico and those of Central America.

The route of the migrations took the Pipils from central Mexico to the Gulf Coast region where Nahuat is still spoken today-south across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and then along the Pacific coastal plain to Guatemala and El Salvador. Some Nahuat speakers continued southward as far as Nicaragua and Costa Rica, where they became known as the Nicaraos. In addition, a few scattered enclaves of Pipils were found in Honduras.

The Pipil population of El Salvador probably numbered close to 1,000,000 on the eve of the Conquest. In addition there were probably at least another 100,000 Pipils in the southeastern coastal region of Guatemala.

The Spanish conquistadors who arrived in Central America found that the territory of western and central El Salvador was actually divided into two aboriginal Pipil states: Izalco to the west and Cuscatlan in central El Salvador. Cuscatlan was by far the larger of the two. To the west of the Izalco kingdom was another Pipil state centered on Escuintla, Guatemala, and between Izalco and Escuintla was a wedge held by the Xinca, an extinct language group that may represent the original indigenous inhabitants of coastal Guatemala. North and east of Cuscatlan lay the territory of the Lencas, possibly the most ancient inhabitants of El Salvador. All these groups were in close contact with one another. Although their relations were often hostile, both the Xincas and the Lencas were strongly influenced by the Pipils.

The name "Pipil" derives from the Nahua pi piltin which means "nobles" or "children." The term has often been explained as a derogatory reference by the Aztecs who presumably regarded Nahuat as a childish version of their own dialect. It seems much more likely, however, that the nobility referent was the more operative one since the Pipils, and other ancient Mexican cultures, were organized socially into noble lineages, and these lineages are yet another typically Mexican feature that the Pipils shared with the Aztecs and other groups of central Mexico.

Political Organization

The noble lineage was stratified internally, specifying its titular head, nobles, and commoners. Commoners were not members of the lineage, but were attached to it and were dependent on the titular head for land. The head of the lineage distributed lands to commoners and nobles in return for tribute and personal service. In the political sphere, the noble lineage formed a close-knit group of kin and subjects. Nobles exercised a wide range of politico-administrative offices. Political connect ions among noble houses were based on common descent from a single noble lineage. Thus, a single lineage often had several noble houses and lords, each with his own land and subjects. This pattern of sociopolitical organization is traced to pre-Aztec central Mexico.

Economic Organization

Pipil commoners were farmers, hunters, fishers, weavers, traders, and warriors. Agriculture was based on the widespread Mesoamerican cultigens* of maize, beans, squash, and chili peppers. Other important food crops included tomatoes, peanuts, avocados, and amaranth. The most important commercial crops cultivated were cacao (chocolate) and cotton.

The hunters and fishers provided food as well as raw materials. The most prominent game animals of the Pipil area included white-tailed deer, cottontail rabbits, tapirs, and peccaries. Objects were made from animal skins, feathers, bones, and marine shells. Before a hunt, a deer would be sacrificed and its heart burned with rubber for the gods. Their method of hunting was to create a circle of fire in the forest, driving the animals to one place in the center. There they would kill their prey with clubs and arrows. In addition to hunting, fishing was also an important means of securing food. The lakes and rivers were abundant with fish which were commonly taken with nets.

Many women participated in the economy through weaving. Pipil women spun and wove cotton cloth from which a wide variety of garments was made. They made inks and dyes using plants and minerals. One plant they used was indigo, which is the source of blue aniline dye. They made red from the bodies of wood lice.

A vibrant system of marketplaces was serviced by professional traders who bought and sold foodstuffs, clothing, and other items. We know about the markets through Spanish documents of the early Colonial period. These same documents tell us what crops and goods were produced and traded.

The Pipil economic system was characterized by specialization in production. An unusually complete tribute document dated to 1532, less than ten years after the entrada of one of Hernan Cortes's most brutal but effective captains, Pedro de Alvarado, and scarcely five years since the pacification of the region, provides details on economic production in the province of Cuscatlan. The data in this document indicate that cotton and cotton cloth were the most important items produced for exchange. Many settlements of Cuscatlan produced maize, beans, and chiles for trade in the marketplace. Very few produced cacao, and this crop was probably a production specialty of the pre-Columbian Izalco state. Other items produced by the settlements of Cuscatlan included salt, dried fish, pineapples, honey, and wax.

Warfare and Militarism

Pipil men served as part-time soldiers, and they were among the fiercest warriors that Alvarado met in the conquest of Central America. Warfare was endemic in south eastern Mesoamerica during the Postclassic period, and, of course, it was through armed conflict that the Pipil dislodged resident populations and seized territory. Warfare for the Pipils, as for most ancient Mesoamericans, was an expression of political force and an important means of social mobility. Military orders were powerful social and political institutions through which highly specialized warriors achieved fame and recognition.

At the time of the Conquest, the Cuscatlan state was at war with the expansionistic Cakchiquel Maya state centered on Iximche, Guatemala. The Escuintla Pipil state was also at war with Iximche. Cuscatlan seems to have been encroaching on the territory of the Izalco Pipil state, and at the time of the Conquest Cuscatlan had taken control of two settlements formerly in the domain of Izalco.

Weapons included atlatls (spearthrowers), lances, bows and arrows, and wooden swords edged with razor-sharp obsidian blades. Warriors protected themselves with thick padded cotton armor which extended to the waist and sometimes covered the thighs. Alvarado described Pipil warriors in a letter written to Hernan Cortes: "The fields [were] full of warriors with their plumage and insignias and with the offensive and defensive arms. To see them from afar was terrifying, because most of them had lances thirty palms long, all raised high." Pipil warfare was closely connected with religion, and no enemy was engaged without the aid of religious prophecy.

Religion

Pipil religion was very similar to that of the Aztecs. A specialized priest hood formed a special caste among the nobility. The priests, who are de scribed in early historical accounts, lived in their temples and wore special clothing and accoutrements that distinguished them from other members of the nobility. Their duties were to perform rituals, to preside over ceremonies, and to act as intermediaries between the gods and the people.

The Pipils worshiped a series of Nahua deities very similar to those of the Aztec pantheon. These deities are well known through ceramic sculptures and figurines, and they are identified through their close affinities with the gods of pre-hispanic central Mexico which are known through the chronicles. Among the most important Pipil gods were Quetzalcoatl (the Feathered Serpent), Tlaloc (the Rain God), Mictlanteuctli (the Lord of the Underworld, the God of Death), and Xipe Totec ("Our Lord the Flayed One," the God of New Spring). These deities were worshiped on different ritual occasions observed in the sacred calendar of 260 days which was correlated with the solar calendar of 365 days to produce the common Mesoamerican ritual cycle of 52 years.

The most remarkable of all Pipil religious ceremonies centered on human sacrifice. Two types of sacrifice ceremonies were described in 1576 by the Spanish judge Diego Garcia de Palacio who probably based his account on an earlier source. The first was auto-sacrifice to extract blood offerings for the gods. The second form of human sacrifice involved the execution of human victims, usually war captives, by specially designated priests. These sacrifices were described in considerable detail by Palacio, and they are also attested by archaeological evidence. It is important to note that human sacrifice is a very ancient Mesoamerican cultural practice. Its elaboration by Nahua groups such as the Pipils or the Aztecs represented an extension of its religious function to the political realm as religious ideology began to play a role in state formation and maintenance.

The Mesoamerican ball game was an important ritual for the Pipils. They built pyramids with staircase sides for their temples. Next to the pyramidal temples were courts for playing the ritual ball game. The ball court was bounded by two large parallel walls with two vertical stone rings, one in the center of each wall. These rings were the goals. At the opposite end of the court were tiers of seats for spectators. The game was played with a solid rubber ball and players moved the ball with their knees and hips, trying to pass the ball through the stone rings, which was very difficult and rarely occurred.

Education

Education was based on the oral transmission of the knowledge obtained through the experiences of past generations. Rulers and priests received formal education in religion and cosmography. Ordinary people probably did not receive a formal education from teachers; rather, they were most likely taught by their parents. This education must have been very effective, since many cultural expressions are found in archaeological remains and close ties to cultural heritage are still preserved among the indigenous people of Central America today. During the Conquest, the Spanish attempted to erase this earlier culture and religion as "idolatry," particularly through the imposition of Christianity.

The Conquest

In June 1524, with the conquest of the Aztecs complete, the Spanish conquistadors looked to the south for new lands of riches. Hernan Cortes dispatched Pedro de Alvarado to Guatemala. He led his 250 Spanish troops and some 5,000 to 6,000 native auxiliaries from Mexico down the Pacific coast of Mexico and into the Guatemalan highlands, where they fought bloody battles against the Cakchiquel and Quiche Maya. The first Pipil groups that they encountered inhabited the Escuintla region of the southeast Pacific coast of Guatemala. After a brief scorched-earth campaign in Guatemala, the Spaniards moved on into El Salvador.

Their first battle against the Pipils in El Salvador was near the modern port of Acajutla, on the Pacific coast. The Pipils strategically situated themselves close to a hill. Alvarado determined that his soldiers on horseback would not be able to attack the Pipils efficiently in this position, so he feigned a retreat. The Pipils, not suspecting that this was a trap, attacked the conquistadores with spears and arrows. They were drawn out of the refuge and into an open field. At this point Alvarado's men turned around and launched an attack on the Pipils.

The Pipil warriors wore protective clothing made of very thickly woven, padded cotton. This precaution proved to be fatal. The stiff cotton armor made it very difficult for the Pipil warriors to get up after they fell on the ground. They were at the mercy of their enemy. Alvarado reported in a letter to Cortes that all the Pipil troops in this battle were killed.

Spanish losses were also heavy, and Alvarado himself took an arrow in the leg which penetrated his thigh and lodged in his saddle. This wound would remind Pedro de Alvarado of the battle of Acajutla for the rest of his life, as it left him with a permanent limp. Five days after the encounter near Acajutla, the Pipils organized another large force near the village of Tacuscalco. The outcome of this battle was, as Alvarado put it, another “great massacre and punishment.”

Thereafter the Pipils shifted their strategy. Rather than gathering in large numbers to challenge the Spaniards on the open field, they engaged the conquistadores in guerrilla skirmishes.

Colonial Domination

The Spanish Conquest led to the incorporation of the Pipils into the European world system. This meant that the Pipils would now produce wealth for the Spanish empire, and their wealth was mostly in the form of agricultural production since El Salvador did not have the precious metals that became the primary objective of Spanish conquest throughout the New World.

A system known as encomienda was established in order to grant land and Indians to Spanish overlords. This institution provided the principal means by which labor and goods could be extracted from Pipil peasants. The most important commercial tribute item was cacao, produced in increasingly large amounts by the Izalco towns. Important and influential Spaniards received encomienda assignments as a form of pension in reward for their services to the Spanish crown.

A small clique of encomenderos who held towns in the Izalco region became extremely wealthy from tribute payments in cacao from the Indians. They not only received the cacao tributes that the Spanish colonial system considered their entitlement, but they also extorted the Indian. One of these cacao lords was said to live as if he ruled his own personal fiefdom.

The cacao industry had run its course by the end of the sixteenth century. Soil exhaustion, overplanting, and climate change combined to bring an end to this lucrative enterprise. By the 1580s, with cacao production already in decline, ranching and indigo (blue dye) production rapidly became popular pursuits in the former provinces of Izalco and Cuscatlan.

Commercial agriculture was closely tied to the decline of most Pipil settlements. In order to survive, many Indians found it necessary to leave their towns and move to the countryside. This trend had started by the middle of the sixteenth century, but with the rise of indigo production and cattle ranching as primary economic activities many Pipils decided to pass from the villages to the countryside seeking jobs and minimal protection from individual Spanish and ladino owners of ranches and indigo mills.

European disease also had a tremendous impact on the Pipil population during the Colonial period. Three waves of serious epidemic disease struck with tremendous mortality in the sixteenth century: smallpox in 1520-21, pneumonic plague or typhus in 1545-48, and smallpox and typhus in 1576-77. By the late sixteenth century the Pipil population was reduced to about 95% of its late pre-conquest level, and it did not fully recover until the late eighteenth century.

Resistance

Pipil resistance to Spanish rule in the Colonial period took the form of conscious and deliberate adaptation to the new conditions of existence, passive resistance couched in the new terms of economic, social, and political interaction. Revolts against the government did not occur until after independence was granted from Spain, and even then they were relatively small-scale.

The most serious revolt occurred in 1932 as the culmination of the alienation of communal lands that began in 1881. The 1932 uprising was centered on Izalco. The peasants organized, as the poet Dimas Castellon Mariano Espinoza describes,

Over there in the hills

en thousand and more

white sombreros

are coming down

Coarse cotton trousers

and sharpened machetes

The peasants evicted

evicting

are coming now

Over there in the hills

ten thousand and more

white sombreros

are coming now

The government's response was the indiscriminate massacre of at least 30,000 Indians--men, women, and children--over the course of just a few days. Peasants were rounded up and tied with their arms behind their back and shot.

The repression of the popular insurrection was a genocidal act aimed specifically at El Salvador's Indian population. Believing that Indians were the backbone of the rural rebellion, General Maximiliano Hernandez ordered his troops to kill anyone that appeared to be Indian, as evidenced by their clothing style and other outward features. Thomas Anderson, a U.S. historian who studied the massacre, stated,

The extermination was so great that they could not be buried fast enough, and a great stench of rotting flesh permeated the air of Western El Salvador.

The memory of this brutal slaughter, known as La Matanza, is still fresh in the minds of many Salvadorans.

Conclusion

Many say that few Pipils survive today. (One estimate is that 2000 speakers of Nahuat live in the Izalco region. ) As a result of the 1932 massacre, few Indians will admit to speaking the language, and most will not wear Indian clothing. Nevertheless, the Pipil heritage of most Salvadorans is evidenced by their culture which remains indelible in El Salvador.

About the Author: Bill Fowler

Bill Fowler is an archaeologist and historian. He teaches in the Department of Anthropology at the Vanderbilt University in Tennessee. We asked him to tell us a little about how he began to study the Pipils and his current work:

While a graduate student at the University of Calgary in the mid-1970s I went to El Salvador to participate in a salvage excavation of archaeological sites that were about to be flooded by the reservoir of a hydroelectric dam. I immediately fell in love with the country and the people, and I found many archaeological problems in El Salvador that deserved attention. After a couple of years on the salvage project I learned about the Pipils and of the need for research on these remarkable people combining archaeological and historical methods. I taught myself to conduct primary archival research and soon was workin gin archive sin Spain and Central America in an effort to bring Pipil history to life.

In addition to the historical research, recently I have been directing archaeological research in the Izalco region of western El Salvador. Some of the problems that we are addressing in this project include the time of the arrival of the Pipil immigrants in this region from Mexico, the role of cacao in the pre Columbian Pipil economy, the importance of irrigation in pre-conquest and colonial cacao production, and Pipil resistance to Spanish colonial rule.

The Legacy of the Pipil Culture

The influence of the ancient Pipil culture can be seen in many aspects of contemporary Salvadoran life. Below are just a few examples. Most of this information is derived from a publication titled: Etnografia de El Salvador published in 1985 by the Ministry of Culture and Communications, San Salvador.

Cooking

Corn has played an important role in both the material and spiri tual life of El Salvador. In pre-Hispanic times, corn was a basic part of the daily diet and it was also an integral part of the religion. Present day Salvadoran cooking reflects the traditions of the ancient Salvadorans, corn playing as important a role today as it did ten centuries ago.

Many traditional foods are based on corn, such as:

tamales

tortillas

atol: a hot drink made of ground corn sauces

chicha de maiz: an alcoholic drink

cafe demaiz: a coffee-like drink made of toasted corn

Also typical in El Salvador are pupusas, tortillas stuffed with pork, cheese, or beans.

Other basic foods which have been traditional since ancient times include beans, squash, and other plants native to the region. Traditional drinks include coffee and chocolate.

Musical Instruments

Many of the traditional musical instruments of El Salvador have their roots in pre-Hispanic customs. In pre-Hispanic times, music was used during ritual ceremonies and other important events such as weddings, initiation ceremonies, etc. Some of the instruments in use during those times were drums, turtle shells, maracas, and wind instruments such as flutes, whistles, sea shells, and trumpets. Many of these had a symbolic character, for example, seashells represented fertility. Pre-Hispanic musical instruments are still in use in many Salvadoran communities and are played during important religious festivities. Other traditional .musical instruments were introduced during colonial times, such as the marimba (from Africa), the guitar, and the violin (both from Europe) .

Health Care

In El Salvador there is an extensive use of traditional medicine, particularly in the rural communities. Traditional medicine incorporates an extensive knowledge about the causes of illnesses which can be attributed to physical, psychological and spiritual problems. Cures often combine the use of plants and herbs with therapeutic properties and specific rituals. Among the physical causes of illnesses, sight and blood are considered important elements. One can have "strong" or "weak" sight; strong sight could cause an illness. Blood is also a determining factor. Many illnesses occur because "la sangre esta mala" (the blood is bad) or ''la sangre esta debil" (the blood is weak.)

The knowledge of the curanderos (healers) is based on a long tradition derived largely from indigenous medicine and in part from colonial European practices.

When a patient visits a curandero, they are asked questions about: what they have eaten in the last few weeks; recent physical exercise; exposure to rain, cold, sun, etc; their dreams and visions; and enemies who may have caused the illness. Their pulse is taken. The office of the curandero includes an altar with images of saints, flowers, candles, glasses of water and offerings.

The curandero plays a particularly important role in rural communities. Here modern medicine is often too expensive. More importantly, modern medicine is often ineffective because it is de-humanizing and lacks a spiritual component.

Just a few of the dozens of herbal remedies used in El Salvador include:

Ajo (garlic): for inflammation of eyelids.

Albahaca (sweet basil): for dizziness

Maquilishaut: Anti-dysentery

Mora(blackberry): Local analgesic for toothaches

Ruda (rue): emetic

Tabaco: Anti-venom

Language

Many words currently in use in El Salvador have origins in Nahuat, the language spoken in the region by the Pipils. For example:

Atol: from Atuli: a hot drink made of ground corn.

Ayote: from Ayut: squash

Cacahuate: from cacahatle: peanut

Caite: from cacti: sandal

Copal: incense

Chirmol: a condiment made of tomatoes, onions, and green chili.

Elote: from elut: green corn

Milpa: from mili, pan: cornfield

Mish: from mishtun: cat

Tusa: dried corn husk

Zopilote: from tzupilot: vulture

Many place names in El Salvador also have their origins in Nahuat. Following are just a few. Can you find them on the map?

Ahuachapán: from Ahuachia Apan: splashing river.

Chalatenango: from Shal, At

Tenango: place of water and sand.

lzalco: from Its, Sahl, Co: place of black sand.

Usulután: from Usulut, Tan: City of ocelots

Coatepeque: from Cuat, Tepet: hill of the serpent.

Panchimalco: from Panti, chimali, co: place of flags and shields.